If you have enjoyed reading The Political Inquiry we would appreciate anything you can give back with a free or paid subscription. All donations received will be put back into the Substack to continue its development. Thank you to those who have already subscribed and donated. Each writer’s views are their own.

Some of our most enduring political commentaries, theories and revelations have originated in cross-country observations. There is something to be said for the clear-natured insights one can draw when not engrossed in the political culture of a country. Here I’ll offer a disconnected, and not overly informed perspective on the American political crisis; loosely defined as a broad and increasingly chaotic questioning of democracy by the world’s strongest nation.

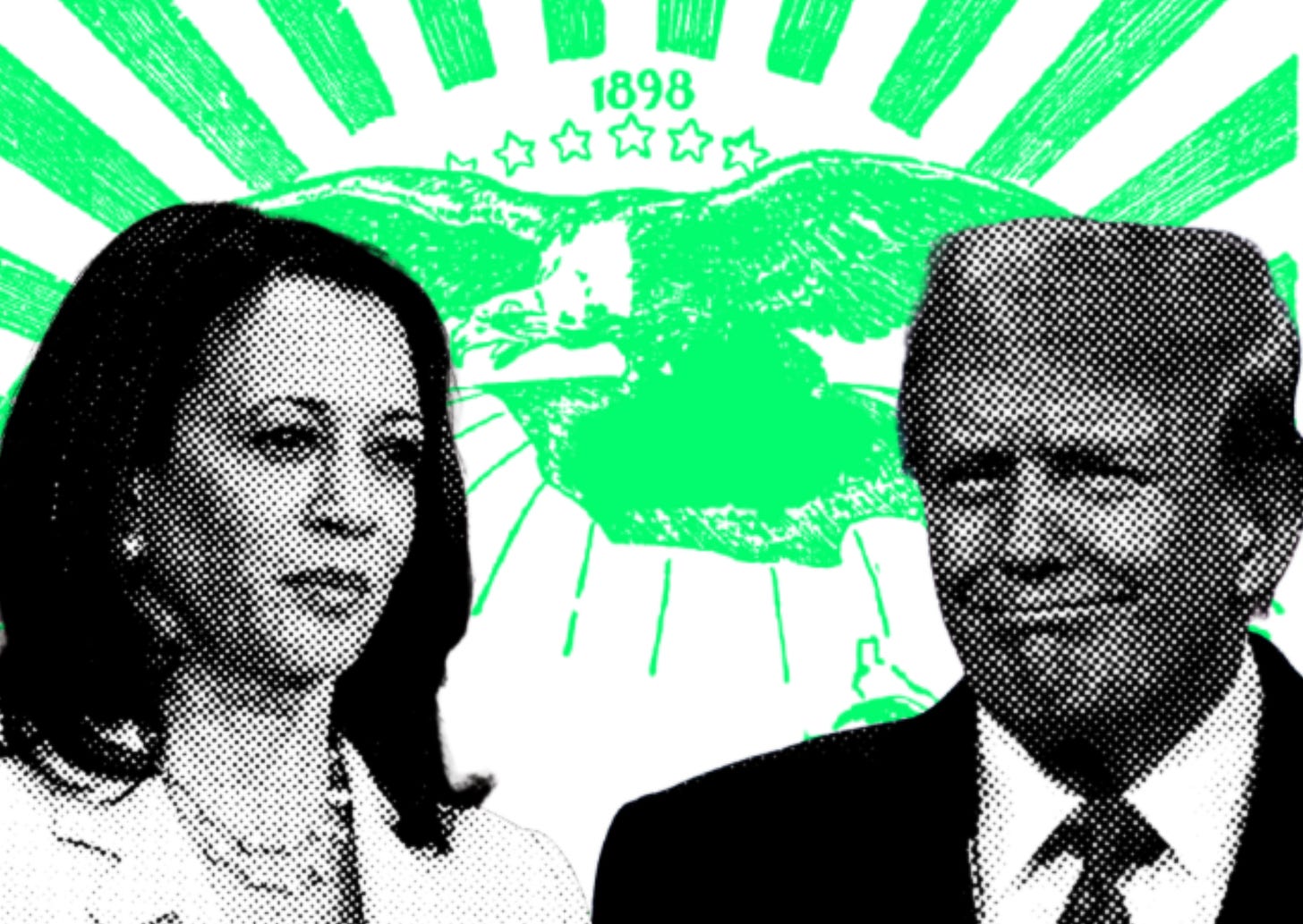

The right, led by Donald Trump, has a very real chance of winning after increasingly authoritarian rumblings and instituting an insurrection four years ago, while the left (if making some governing progress) continually defends a structure of US governance that prioritises power over the people, creating an ever greater disconnect. American democracy seems at its greatest peril since the 1860s. But for all these dangers the American problem remains a perplexing historical conundrum for a system that, broadly, is still working (particularly for some of those trying to tear it down).

A Different Politics

There is much to be said for Marie Le Conte’s quotation of President Lula of Brazil:

“They think that the poor don’t have rights,” he told them. When sworn in as president, he promised that he would fight for their rights – “the right to barbecue with family on the weekend, to buy a little picanha [a cut of beef], to that piece of picanha with the fat dipped in flour, and to a glass of cold beer.”

And Le Conte’s deft take:

The reason I love that quote so much, I think, is that it is truly joyous. It is from a politician who recognises that life isn’t wholly about the place you live in and the job you have and the taxes you pay. It’s also about having a good time while we can. Who in the UK’s national mainstream politics is making that offer?

While there may not be anyone making this human-grounded political offer in the UK, at least for now, this country has remained, through astoundingly dismal times, reasonably stable. There is something very stereotypically British about that – the joy of political discourse is nonexistent. Bravado is deemed as arrogance, fun as lies. While Brexit produced a momentary ignorance of the boring doctrine with Boris Johnson, the British public’s trade off was clear and no lasting endorsement of this style.

Johnson’s implosion has only reinforced the nation’s detestation of political performance. Compared to the hyperbolic recasting of Kamala Harris, only a few months ago deemed by the Democratic establishment as boring and crap, Britain is inherently more akin to Germany’s gritty style than America’s political flamboyance. It is this American faux-joy – born of reality TV – that papers over cracks of a system lacking democratic connection – and misunderstanding the challenges of its own reality. And in one respect, who can blame them? The balancing act to accommodate a trucker in Wyoming to a teacher in Massachusetts is difficult. That's before considering the other 333 million people while simultaneously attempting to control the world’s geopolitics.

But there is something more obvious in this appeal to human needs – an obvious physical appeal to the security of food – the security of pleasure – and fundamentally life. Whenever politics delves into the realms of chaotic upheaval and revolt economic problems are almost always present. The alarming point raised by the ensuing political crisis in America is that their economic growth is the best in the G7. Inequality may be rising, and the systems of healthcare, justice, housing, social mobility, and welfare are far from adequate, but income is broadly increasing and at high levels. Compared to the rest of the world, particularly the global south, this is a state of luxury. It is, in short, an economy, and an empire, in which enough of the population are winning in order to maintain its legitimacy. There is strikingly little politics of food.

System Failure

One does not get the French Revolution without a dire economic question of finance and food; the crops failing, the bread price doubling and decades of financial mismanagement and inequality. The economic right to bread and food became synonymous with political control and representation. Nowhere as evident than in the American Revolution – with the much vaunted sugar tax. The other aspect revolutions ignited from is the very essence of life – a level of freedom from oppression – the Haitian Revolution, the landmark moment in this refrain, but also evident in the French and later revolutions. The British Glorious Revolution offers no soothing connection in this regard: an example of (yes) an autocratic overthrow, but more so a conservative revolution against catholic freedoms and a trigger happy king – there was no whiggish plan to transition to full democracy, as it was later described.

Our missing element for today’s America is the precedent from transitioning from a two-hundred year old democracy (shorter if you start at equal voting rights) to autocracy. Obviously ancient Athens is one example – though the level of enfranchisement (no slaves, foreigners or women), the fact it was a city-state and its direct nature of democracy destroys any serious comparison. The Roman Republic gets closer but can hardly be labelled a democracy – more an oligarchical-democratic mismatch of power sharing. But the Republic’s destruction raises an alarming point, as Mary Beard notes: “the [Republic’s] empire created the emperors, not the other way round”. It was not so much the actions of, say, Julius Caesar or Augustus that were solely responsible for its transition, but the challenges of empire. The questions of a military-state, vast amounts of new land and wealth, and powers of the state mixing incongruously with rising inequality, allowed the Populares (a nascent form of populism) to weaponise the demands of the people and establish autocratic power.

The more modern examples of democratic failure have occurred largely due to economic ruin – the Wall Street crash, the obvious 20th century example which crushed several European democracies with it. But also the question of war and ideology – the Treaty of Versailles, Hitler, Stalin, Communism, Facism etc, etc. These were big, broad concepts of overlapping territorial and political issues that mixed a very modern view of Europe (and humanity) with the very ancient drives of power, conquest and European control. Again, there is little direct similarities here to the current US predicament. American political and social culture is still remarkably isolated in comparison to Europe. But if there is one obvious line through all these examples it is this: an excessive drive for power, against the wishes and needs of a population or continent, is almost always unsustainable.

Revolution in the Empire

The dramatic absence of economic motives place America’s problem as a particularly organic virus infecting the body politic. It's said that a democracy always needs autocratic or authoritarian elements to maintain itself, while an autocracy requires the language and perception of democracy to sustain itself (though in reality an autocracy merely makes trade off with stakeholders in a similarly democratic way). So one can expect some authoritarian elements to creep into large democracies, granted they validate the overall aim of maintaining a reasonable-to-high level of democratic control.

America's young age and new democracy certainly induces many into an ignorance of time’s potency. It's arguable that only after 1945 America became the world power (if ever increasing from WW1 onwards). Is 75 years really much time in the grand scheme of history? Of course not. There has been a golden age of American power, lasting until the 1990s, in which the state actually showed very minimal signs of authoritarian control. There were very few trade-offs (bar tax or the draft) which Americans were forced to make to maintain global hegemony. This era ended with 9/11, and the successful campaigns but failed wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Since then the international system has become much more multi / bipolar, with the rise of China and the global South, as well as resurgence of Russian aggression. Until now, however, these problems have not seriously affected the politics of the nation.

However, to run an empire, and definitely when the hegemony of said empire is under increasing strain, requires an escalating level of strikingly anti-democratic tactics. The cliche is that the rise of terrorism and 9/11 precipitated the increase in authoritarian methods to guarantee the safety of democracy. But in reality the increased level of monitoring, control and general anti-democratic dealings had been present since WW2. The only change was that while the CIA and State Department controlled or monitored most of the world, particularly ‘elections’ in South America, the Middle East and Europe, 9/11 brought imperial tactics onto home soil. These days the FBI and Homeland Security, with incredible methods of population monitoring, essentially break the 4th (and possibly 5th) Amendment every second, yet this is not a politicised issue in the US – until now.

Trump’s American vision, if one can even call it that, is obviously conspiratorial and largely misguided. But if there is one section which offers a glint of innovation it is the attacks on what he calls ‘the deep state’. In essence, his attack is on the bureaucratic behemoths that run what we term the American empire. Department and agency manpower numbers in the millions (for comparison, the entire British civil service is 500K), each with vast resources and institutional staying power. They all prop up what we term the ‘military-industrial-technology’ complex that underpins American power – ranging from Washington, to Wall St to Silicon Valley. Not since Kennedy, and before that FDR, has there been a president that rocked the underlying system much.

What Trump’s attacks on the deep state achieve is a linking of its failures to the current health of American democracy. Democracy created the empire, and for this democracy (those in Washington – aka ‘the swamp’) must pay. The conflation of the two is highly dangerous. An empowerment of the people by ending wars, such as Ukraine, is just step one of a Trump doctrine. On a fundamental level Trump is identifying the core issues with running an empire – the degree of authoritarian oversight, the prioritisation of complexes of power, and the degradation of the citizen’s voice and pocket. What is revolutionary in Trump’s message is not simply a desire to reduce or destroy the military-imperial control over the state but to do away with the whole system – particularly its democratic parts. Trump as emperor is the fix, not a new democratic system based on reform.

Onwards

But the real question is whether Trump would carry through his reforms – and how? Would he really have the governing and intellectual ability (as well as advisors) to control the powerful state that runs the empire? Can he actually get away with firing the top 5% of leadership in each governing agency? I doubt it. His attempts to do so may trigger a crisis, a counter-revolution from within, one so destabilising that it creates a period of autocracy on either side (though there are many steps before this happens). For the left, if Harris does win, there will be a continuation of current democratic politics with a subtle tilt to the left.

But for how long can the Democrats run on an establishment line that defends a state which increasingly sacrifices its population’s wishes for the demands of empire and global control? The tenants that uphold the American empire (Wall St, Silicon Valley, Military-Industrial bureaucracy) are inherently antithetical to the foundations of its party and politics, as (whatever your views on it) the Israel-Gaza conflict has illustrated. It is possibly antithetical to modern democracy itself.

If the left are to grapple control of the Democratic party, likely through Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, it may too begin to question the role America plays in the world – which in turn questions the domestic political control of its bureaucracy at the expense of its democracy. A return to American isolationism does not necessarily translate into a disintegration of American democracy – but a Trumpian transition away from it, or the continued linking of democratic and imperial systems may mean the American crisis is about to explode. This will not simply end with Trump or Harris.

Tom Egerton is a political writer and researcher, his new book The Conservative Effect, co-edited with Anthony Seldon and published by Cambridge is OUT NOW, you can order it here: with Cambridge, Waterstones or Amazon. Follow Tom on X / Twitter here.

Excellent piece, particularly in the wake of last night's debate