GE Updates #5: Cockup and Conspiracy

The deluge of Tory political scandals has had a lasting effect on the nation and its politics.

If you have enjoyed the reading The Political Inquiry we would appreciate anything you can give back with a free or paid subscription. All donations received will be put back into the Substack to continue its development. Thank you to those who have already subscribed and donated.

After every scandal a government faces we return to the same dichotomy: cockup or conspiracy? We ask ourselves: were those politicians so shortsighted to make such a callous mistake, or were they so morally bankrupt to think they could get away with it? The last three years have seen a precipitous increase in the number of political scandals. Whether the three P’s under Boris Johnson (Paterson, Partygate and Pincher), or the series of sleaze-triggered by-elections which have contributed to the Conservative Party’s rolling demise, scandals are no longer rare moments of intrigue, but are instead a regular part of political life. This says much for the 2010-24 Conservative effect on politics and our institutions.

The most recent scandal, in which several senior conservatives who knew the election date proceeded to illegally bet on it for their own gain (to the tune of thousands of pounds) is one of the most egregious yet, both for its arrogance and moral disregard. It's clear we longer have to choose how we now describe Tory scandals: they are momentous cockups after failed conspiracies.

Naughty History

Prime ministers have never been holy paragons of morality. The politics of the eighteenth century, and large parts of the nineteenth, was determined by how much corruption (or sleaze) you could get away with. The first PM, Robert Walpole, was defined by his systematic corruption and surpassed most in this capacity. Walpole fixed elections, distributed patronage and paid allies, through his supposed euphemistic ‘Secret Service fund’, building a deceitful network which was vast and highly effective. None since have been so institutionally corrupt, and while his actions were defined by the political time, his impressiveness is the ruthless nature of his conspiracies, rarely ending in cockup. Walpole’s premiership is considered one of the strongest historically; defining the outlines of the office of prime minister and its power over the monarch by controlling parliament.

Since Walpole, scandals have mostly been a series of cockups. The most salacious was the 3rd Earl of Bute who was caught in bed with the Dowager Princess of Wales which partly forced him to resign in 1763. One of the funniest, and certainly my favourite, is Portland in 1809 who resigned after allowing a duel between his Foreign Secretary George Canning and Secretary of State for War, Viscount Castlereagh. Now, I’m not advocating violence, but one wonders if duels may have been a more effective mechanism to reconcile Conservative divisions over the last eight or so years of government.

While David Lloyd-George’s impressive premiership was brought to an end partly through his scandalous lifestyle, particularly his viscerally corrupt Cash-for-honours innovation, questionable press baron relationships and fatally his £1m advance on his war memoirs while still PM, Macmillan is our most popular example. Most may know of the famous 1963 Profumo scandal, in which Defence minister Profumo became involved in a love triangle with Kathleen Keeler and Soviet naval attache Yevgeny Ivanov. Profumo, along with his mishandling of the Vassall affair, hastened his resignation.

It's fair to say that conspiratorial scandals have become rarer since the late nineteenth / early twentieth century, as the legal system and cultural conventions strengthened against overt political corruption while social norms slowly liberalised. The point of taking a quick look at the history of prime ministerial scandals is to note that never in British history has there been a time without them. But while there have always been scandalous cockups and conspiratorial plots, they were few and far between. The other key difference to today is the moral and political mistakes almost never occurred simultaneously: if there was a moral failing, the minister or MP usually resigned or was punished. There was rarely a concocted cover up or flawed defence of mistaken actions.

A Dime a dozen

So now we return to our main proposition: the modern Tory scandals have transformed into both cockup and conspiracy. Take Johnson’s premiership, for instance. The Owen Paterson scandal, in which he was paid £50k to lobby the department of health to award Randox a £133m contract (and after another £347m) without declaration, and later the Food Standards agency on behalf of Lynon country foods. He was, in other words, a lobbyist first and MP second. For some indecipherable reason Johnson decided he should whip his MPs to oppose the (fair) 30 day punishment which Paterson was to face, determined by Kathryn Stone’s Standards Committee. Fury ensued and Johnson was forced to U-turn after opposition parties boycotted the entire parliamentary standards system. The simple moral cockup was transformed, overnight, into a political conspiracy: Johnson trying to use his power to protect his corrupt mates.

Johnson’s partygate, in which he, along with senior civil servants, allowed (and to a degree attended) parties in Downing Street while the country was locked down, was a striking mix of immoral actions and pathetic cover-up once the story broke. Its no surprise that Johnson’s final scandal, in which he attempted to defend his whip Chris Pincher who had a history for alleged sexual assault (and which Johnson himself had nicknamed ‘Pincher by name, Pincher by nature’), led to his dramatic 48-hour demise in which so many ministers resigned he was physically unable to form a government (around 200 MPs). His party had had enough of what they saw as a conspiracy to defend cockups – and, indeed, cocked-up defences of conspiracies. The two had merged.

There was also Johnson’s enforced resignation from the Commons after the committee published this about his consistent truth-twisting in the House:

1. Deliberately misleading the House

2. Deliberately misleading the Committee

3. Breaching confidence

4. Impugning the Committee and thereby undermining the democratic process of the House

5. Being complicit in the campaign of abuse and attempted intimidation of the Committee

Rumbling throughout the Johnson-Truss-Sunak premierships have been a considerable number of scandals which have triggered by-elections. On my list, I have: Paterson (lobbying scandal), Imran Khan (convicted of sexual assault), Neil Parish (porn in the Commons), Johnson (Johnson scandal), Nigel Adams (Johnson scandal), Nadine Dorries (Johnson scandal), David Warburton (drugs and alleged sexual misconduct), Chris Pincher (alleged sexual assault), Peter Bone (bullying and alleged sexual misconduct) and Scott Benton (lobbying scandal).

PMs cannot be held directly responsible for these actions, but there still remains a connection to the leadership. Who gets selected, what culture and standards the party cultivates, how the parliamentary party / whips acts, and how one deals with scandals are all set from the top. The Whips system is in effect each party’s HR office – and it is in conjunction with the leadership which sets the rules and monitors the behaviour of MPs. Thus many of these supposed cockups are partly a conspiracy of continued moral and cultural disregard.

A good example of why this is a new phenomenon is John Major, the last Tory PM to oversee a landslide defeat and exit into opposition. What Major also experienced was a slew of sleazy MPs and painful resignations. While a lot of these weren’t directly his fault, some of it can be attributed to the party seeking to hold onto office by preventing instability / by-elections (as he had essentially no majority). But Major’s policies, some in reaction to the sleaze, was to introduce a series of moral reforms on how to improve standards in public life, including the Nolan principles, the Questions of Procedure (which became the Ministerial Code) and the Civil Service Code. Hennessy argues that, in the short term, this held his party to a higher standard, thus triggering more scandals. But in the longer term the impact is an obvious positive on how we judge public life – and one that marks Major’s moral character out in comparison to the Johnson-Truss-Sunak period.

Betting the House

The cumulation of these scandals have created a highly-dangerous point for our politics and the Conservatives. The news from the Sunday Times that there is a fourth senior Conservative under investigation for illegal insider betting on the election date is staggering. The current Tories we know under investigation reads:

Nick Mason – Chief data officer, Craig Williams – Parliamentary Private Secretary, Tony Lee – Director of Campaigning and his wife Laura Saunders – candidate in Bristol North West. What's more shocking is what the Sunday Times next said:

The Sunday Times can reveal that the three Tories already known to be under investigation are not the only ones.

The commission’s inquiry, which is looking at any bets placed before May 1, has identified several more people who may have placed bets while having first-hand knowledge of when the election would be called.

The watchdog’s inquiry is split into two parts, with these people — said to number fewer than ten — categorised as the “first wave”.

Not only have several senior Conservatives been engulfed in a highly illegal scheme to make a quick buck from their insider knowledge, but that they are likely not the only ones. There is a rumour circulating, one which I’ve now heard numerous times, that there are some closer to No.10 that may be implicated. Gove’s statement yesterday that this is ‘as damaging’ as partygate illustrates the disillusionment their best performing minister feels. The facade is broken, he knows the game is up.

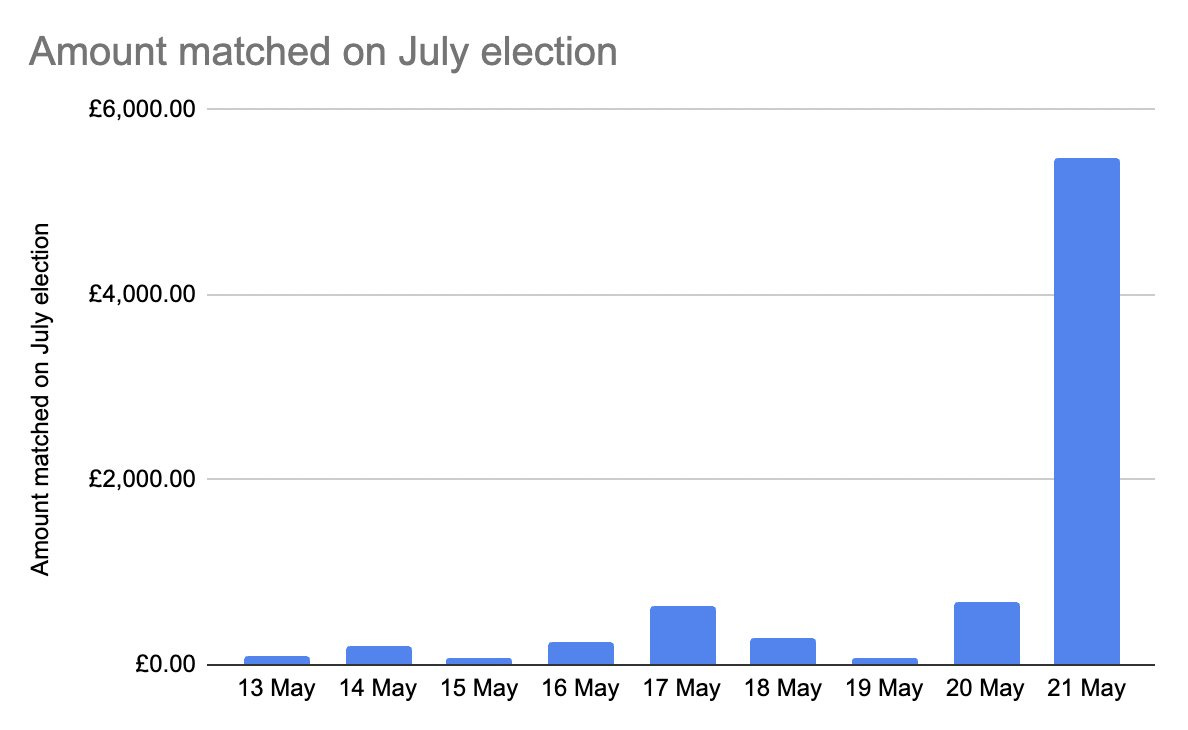

The scale of the betting seen in the day before the election, as noted by Jim Waterson, would certainly suggest a wider scandal is about to explode:

The 21st was the day before the election was announced – and it sees an auspicious spike in betting, most of it likely fuelled by insider knowledge. The level of betting was so substantial that it started shifting the odds, which alerted Morgan McSweeney, Labour’s Director of campaigning, that there was likely a snap election to be called – something innocently revealed by Gabriel Pogrund four weeks ago.

All this amounts to is a continuing increase in political scandals, in large part due to the last three years of Conservative rule. What began as fraught government conspiracies; defending lobbyists, shielding those responsible for alleged sexual misconduct or cultivating a senior leadership who deem insider trading acceptable, have all ended up as incompetent cockups – with costly resignations and the near-complete moral defenestration of the party of government.

Trust in the process

These scandals matter. Trust is a fickle resource within a democracy, especially at times of global strife, economic downturn and rising inequality. Without trust democratic politics and processes cease to function. To think the United Kingdom is immune to an extreme anti-democratic or populist turn is foolish – most European countries we once looked to for inspiration of a better politics are trending this way, whether France or Germany. The destruction of the Tory party by its own hand may be desirable for some, but what comes after it is unlikely to be more constructive or conducive to restoring trust.

The nation, lacking trust and feeling pain, stares down the barrel of another callous government scandal. It won’t treat the Conservatives lightly.

Tom Egerton is a political writer and researcher, his upcoming book ‘The Conservative Effect 2010-24: 14 Wasted Years?’ is out on 27 June 2024, published by CUP and co-edited with Anthony Seldon. Follow him on X / Twitter here.

Craig Williams is Parliamentary Private Secretary rather than Principal Private Secretary.