Consensus and Power #1: Tides of Time (REDUX)

A series on the power of consensus politics and how effects our ruling system over three levels

The following is a REDUX piece on Consensus theory and a specific interpretation of it. The views shared are open thoughts / musings and not stubborn conclusions or beliefs. This was republished with a few small edits and title changes on 24/06/24.

Power Matters

An admirable, if impossible, ambition of this series is to unify parts of academia and reality: firmly enticing the reader to use abstract ideas in everyday thought. In other words: creating ideas for outcomes, not just abstraction. In short, elections are the easiest form of translating the influence of the people into the form of power in government. Leaders win or lose, with large or small majorities mirrored by crushing or narrow defeats. While this is an important lever in our system, it is not the only way power is manipulated. Power can be targeted directly by influential groups, individuals, ideas or forces – both domestic and global. Power is decided and exercised in numerous arenas, from a myriad of sources – and almost always out of sight.

Due to its obscurity, power and its theories (whether Dahl 1961, Bachrach and Baratz 1970, Lukes 1973) are cruelly disregarded in popular culture; left to the warped minds of conspiracy theorists or left abandoned in academia. The modern world is suffering from low-quality information overload, suffocated by constant existential threat and, as a result, is generally impulsive. Populism, conspiracies and the tyranny of status-quo politics are all symptoms of the same problem: a general misunderstanding of power, resulting in a misdiagnosis of how to solve the problems of the world. It’s thus important to imagine power in the modern world through large, if imperfect, theories of power. Only through confronting how power works can anyone seek meaningful and lasting change. Consensus theory offers a route to doing this.

Consensus: The Analogy

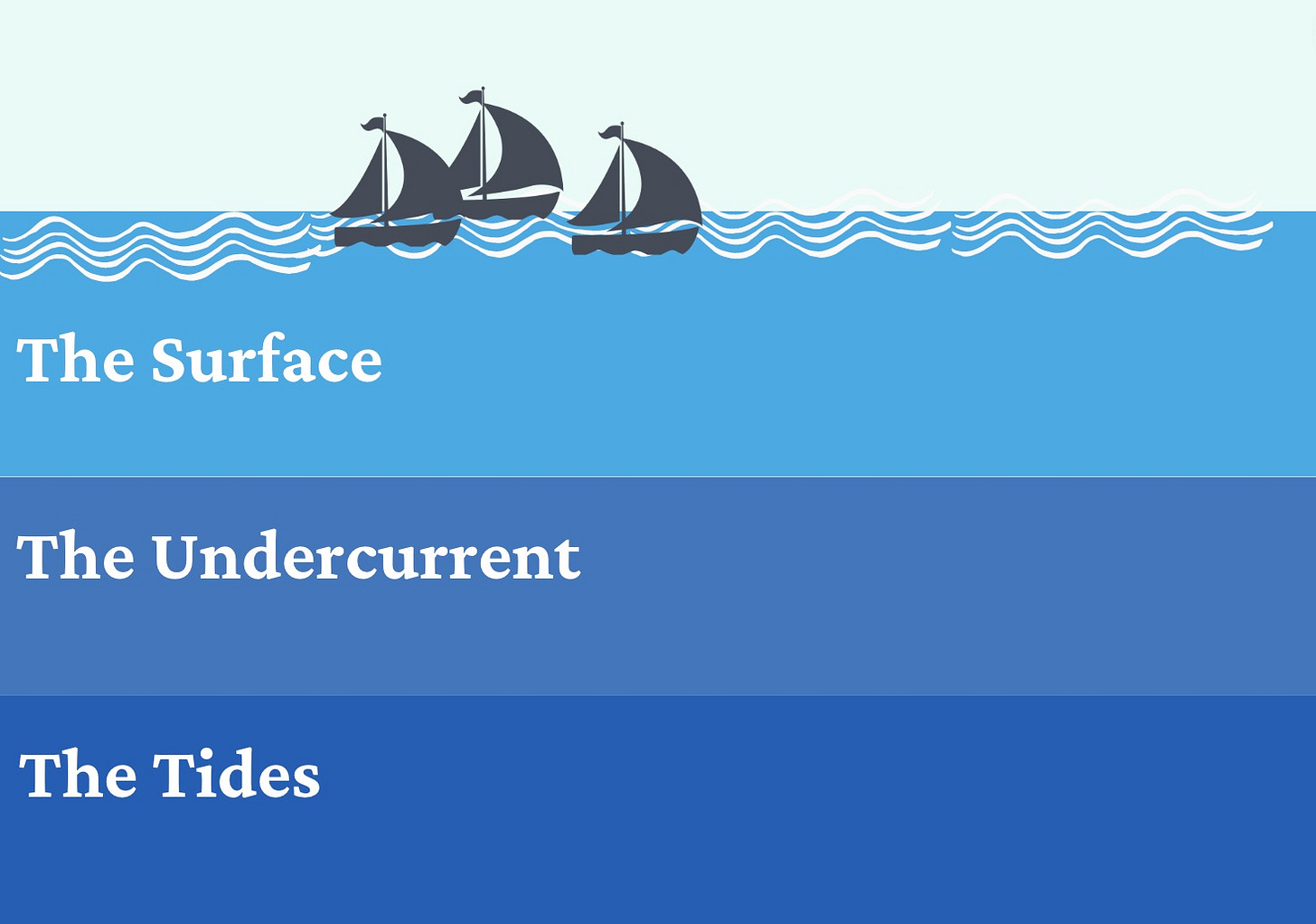

Consensus power is very complex, with numerous different forces acting at different levels and over different time frames. It requires an economic, political and, ultimately, historical lens to analyse. For this series, it’s best to combine these lenses of power into one: the degree of change and its impact on the UK. To bypass this bewildering difficulty, I’ve simplified the different areas where power acts into three tiers using an analogy to tie it to a tangible image. This framework is crude, but it is a start. The analogy, inspired by Jim Callaghan’s famous quote (and based off consensus theory) used is the sea:

“You know there are times, perhaps once every 30 years, when there is a sea-change in politics. It then does not matter what you say or do. There is a shift in what the public wants and what it approves of. I suspect there is now such a sea-change – and it is for Mrs Thatcher.”

The key powers that drive the sea are not what happens on the surface: I.E the surfers, swimmers, ships, waves or calm waters. (NB: ignore the scientific / practical mistakes in this imagery but just accept the broad premise).

Instead, the real powers that change the sea (strength, height, direction etc) are the tides. Tides control how the currents flow, and the currents determine the forces felt on the surface. In reality the tide changes twice a day. In political reality the tide changes roughly twice a century. They are the deep, structural forces within our systems of power and government on which everything is decided and built. The foundations of power.

A good way of imagining the power of the tide is through the analogy: you cannot launch a boat on a low tide, just as you cannot argue a political idea when it's outdated / out of trend. Neither can you row against an opposing tide easily, just as you cannot win an election if it's against the political trend. Tides are key as they decide what is and is not politically possible – influencing both those in power and those which decide power (the electorate). Tides define the currents, which in turn define the surface of politics. The key point is everything originates in the tide.

In the following pieces we’ll be exploring the other arenas of power. For now, we’ll focus on the tides which act as 40-year cycles in politics. (NB: the use of the word ‘Tides’ is interchangeable with ‘Cycles / Consensus’.)

The Tidal Framing: 40-year cycles

During a 40-year cycle, most major political ideas and policy are agreed – or more accurately a truce. Different government’s act broadly on the same principles, and electorates broadly elect governments with a shared vision of what society’s priorities should be; always based on the political tides of the day.

What is key, and how change occurs, is when these cycles break down. A collapse of a cycle originates in a fundamental political or economic flaw within a system – what results is a mini big-bang, or for the purposes of our analogy a tidal wave / tsunami. This tidal wave is usually a global crisis, which has specific and enormous domestic repercussions. Out of this crisis, a new tide is born which completely shifts how power and society works, alienating and transforming both a nation’s government and the minds of voters.

Cycles are similar to Hegel’s Dialectics (see Encyclopaedia of Philosophical Sciences and Philosophy of Right) – In short: the present feeds the past which in turn feeds the future and so on. A better description (and application) of Hegel’s dialectical history can be read in Philip Gould’s book on electoral politics: New Labour: The Unfinished Revolution. The most recent major work on consensus theory is Phil Tinline and his Death Of Consensus [tides], in which he describes Consensus forming due to collective nightmares (especially in the deconstruction ‘crisis’ periods).

The Two Modern Cycles

The last 100 years can be summarised into two cycles, originating out of two crises. The crisis of World War 2 and the great depression (1920s-40s) were a result of the political and economic consequences of World War 1. WW1 introduced the idea of total warfare necessitating conscription, mechanised warfare and nationalisation of the economy. This had dramatic consequences on the world economy and the nature of politics – namely the enfranchisement of the UK population and the heavily debt-burdened state. As Weldon contends (in Muddling Through), this is when the citizen and the state unified in a political and economic union, revolutionary because citizens, for the first time, were personally intertwined with the government's debts (through bonds) and, obviously, health (with their lives on the battlefield).

Out of the ashes of WW1 a new tide emerged; centralising around Keynesian demand management and full employment, a unique antidote for the destroyed economies of the depression (Wall St Crash / debt overload). This new tide, as they all do, contained a substantial political offer of welfare, jobs and security to the newly enfranchised voters who desired more protection, in return for their sacrifice to the nation. While FDR’s New Deal illustrated then new political-economic consensus of the next 40-year cycle, only the conclusion of WW2 could create the space for a shift in UK politics.

Post-WW2, the Attlee’s government oversaw the creation of the welfare state, NHS and national economy – as full employment became sacrosanct, with a general balance reached between the classes in society. This power consensus based (loosely) in Keynesian economics became so influential that it was nicknamed, in the 1950s, ‘Butskellism’ in the– a merging of the name of the Tory chancellor Butler and Labour Leader Hugh Gaitskell because their policies (and ideas on power) were so similar. Politics was fought over how many houses you could build (Churchill 1951) or how low unemployment could be made (1970 Election). The media and electorate were aghast when, for the first time since the depression, unemployment hit a mere 1 million under Heath’s government – a number now seen as incredibly low. The national citizen was paramount.

Roughly 40 years later, in the 1970s/80s, the post-war cycle of Keynesian post-war consensus broke down. Stagnant growth and high inflation plagued the UK – a mix of surging oil prices and ageing, uncompetitive industry caused what's known in economics as a balance of payments deficit (though the route cause was the unfair Bretton Woods system, with the pain placed on debtor nations of such as the UK). Put simply: the UK’s internal consensus was breaking, with Trade Union national industry politics and full employment became two irreconcilable principles to upkeep in times of inflation and recession. As seen with the 1920s-40s crisis, another new political-economic tide was born out of crisis: Neoliberalism. The old empires of Europe had become uncompetitive: fat with consumerism and post-war euphoria. The solution was found in the harsh sting of the unfettered market, with the intention to kick bloated public industry and broken political-economic system into the new era of private opportunity, small government and enterprise.

Under post-war Keynesianism a degree of equality for citizens was the aim – the improvement of the voters as a whole (nation). In contrast, Neoliberalism flipped this: with market consensus now seen as the true imperative (see the ousting of Truss, SOP#10). Less regard is now given for public-facing metrics like employment, investment, government intervention or nationally owned bodies / companies. Instead, the market decides what is and isn’t viable or desirable. This is not just within powerful groups – such as business leaders or government officials – but also within certain voter groups. Because Neoliberalism changed the very power structure of politics and economics, culturally our world shifted as well. Consumerism and materialism are more valued than the health of society or the community (though this is changing). Individualism – synonymous with Neoliberalism, is the watchword. Therefore, voters vote on the government’s perceived ‘economic competency’ (which is another way of saying its performance and viability within the domestic and international market). This is both out of fear of bad governments causing market crashes, and for what governments can put in a specific voters’ pocket. In effect, an electoral marketplace. This ‘economic competency’ metric is the most accurate predictor of election winners since the dawn of Neoliberalism. Thus, the tide has shaped power.

Ponder this:

40-year cycles (tides) are pivotal because they affect the causes (undercurrents) and thus consequences (surface) of politics. Ask yourself these questions when reflecting on how tides impact UK politics:

What ideology does a party / Prime Minister prefer (Thatcher, Attlee, Wilson, Cameron)? What are the norms / accepted economic-political conventions of current politics (nationalisation, privatisation, austerity, fiscal rules, monetary policy, amount of borrowing/ debt)?

Why does a leader / PM fail miserably if they go against conventions (current tides) of politics (Corbyn, Foot, Hague, Truss)?

Why (and how) does the electorate fundamentally realign during some elections, and not in others (Key change elections: 1945, 1964, 1979, 1997, 2019)? Why do the international events (tide crisis) in the world affect power and the very basis of our lives (WW1/2, 1970s crisis, COVID, 2022 Ukraine energy crisis)?

The answer to all of these, in part, is that underneath the insubstantial churn of everyday politics are the tides that really drive change or determine the continuity of ideas and power. They are akin to tectonic plates that only become apparent on the surface when a volcano erupts, or an earthquake occurs. That earthquake in politics is a change in tide: when everything we thought was a given becomes up for debate.

Other Tides?

Yes, there are numerous other cycles that occur and are important. However, for this series TPI is focusing on the key driving tide of power: namely political economy throughout history. Economics (and the distribution of money between empires, nations and people) and politics (control of decisions, rights, violence and war – see Clausewitz) are the most influential forms of power. Through history they reign supreme.

This is not to say that other types of power aren't key: I.E the power of geography determining resources, the power of culture / society on the individual or the timeless power of scientific / technological discovery. However, our system, the power of politics and economics determines much of the meat and bread of power.

R&D investment translates, roughly, into scientific progress and discovery (Manhattan Project, Koch Vs Pasteur or the Industrial Revolution). Invasion or money allows a nation to attain resources or land (British Empire, China’s Belt and Road or the power of the US Dollar). The history and (in)stability of political institutions determine the nature of a society or culture and equality between individuals (US race relations, Cuban isolation or Chinese society). Thus, the tides of time, the foundational cycles of history, are focused on politics and economics: the forces which drive power and decision-making in our world system.

To Conclude…

Condensing hundreds of years of history and change is impossible. However, this analogy does offer a basis on which to observe power and change. It illustrates on what foundations political and economic decisions are made, and how in turn the decision makers themselves (and the electorate) are shaped. In the following parts of this series TPI will connect the elusive tides of time to the more tangible conduits (undercurrents) and consequences (surface) of politics in the UK. However, without understanding the foundations of power, analysing it is impossible. Truly analysing power is not observing what happens, but why and in what form.

If you take away one thing from this piece on tides it's that: the basis of every political decision, and power itself, is thought-up and completed on the basis of these cycles. Well, possibly.

If you enjoyed the piece a like or a share goes a long way!