Consensus and Power #5: Exploring a New Consensus (REDUX)

After the death of the Neoliberal tide, what could come next?

Catch up on the previous piece here

The following is a REDUX piece on Consensus theory and a specific interpretation of it. The views shared are open thoughts / musings and not stubborn conclusions or beliefs. This was republished with a few small edits and a title change on 07/01/25.

Neoliberalism is dying. What comes next? Every new tide (political-economic consensus) is built on the failures of the last. Neoliberalism’s individualised power first died electorally between 2015-19, and then economically between 2020-24, having never truly recovered post-2008 crash. Both the decline of capital investment and the increase in regional inequality within the UK have created a chasm of lost potential and productivity (growth). The globalised market has, while alluring, proven dangerous – with the spectre of geopolitics and pandemics adding to inflation and a national decline.

Out of the ashes of these failures, a new vision for the country is born. At every juncture, there are a few routes that can be taken. The last major choice was in the 1970s, between Thatcherism and Bennite ‘bunker’ socialism. This piece seeks to sketch out the beginning of a new British political consensus that could emerge over the next decade. What’s important to note is that these are just ideas and sketches — a snapshot of where things seem to be going. We expect many of these aspects to be contingent and evolving, and importantly contain no direct party political affiliation.

The State is Back in Town

Increasing economic productivity is one of the big questions of our times. The country’s productivity has stagnated since 2010, harming wage increases and tax revenue. The failure of the market in this is key. Too often businesses are focused on short-term extraction of profit and quarterly targets over investment in wages and technology. But the political establishment must also take a large share of the blame: why have we let the politicians become so lazy!?

As stated in the previous piece:

“Simply deregulating the market and ‘releasing’ the individual for 40 years has created a key weakness in the country: the government has forgotten how to innovate nationally.”

Even with the cash cows of QE the political establishment has languished. The idea that the state can’t do anything or that the market always beats the state has infected the minds of a Westminster elite lulled into a dozing sleep, drunk on superficial power. The state and the private sphere each have strengths, but one can’t function properly without the other.

So, to find a tide that comes after neoliberalism, an active state and political establishment is key, because fixing neoliberalism’s mess (dangerous + short-term markets, underutilised individuals, and a broken state) will require facing it head-on. Did no one question why sending our brightest minds into the city to make millions or into the labs to discover great things would leave the talent pool of leaders fairly shallow? The British state forgot to keep enough clever ones to rule – instead, the power-obsessed and tirelessly narcissistic are left. Not interested in ruling, innovation or reform, the narcissists would rather relax and watch the country diminish, crying “but the market will save us!” while they worry about their standing in The Telegraph.

Tony Judt summarised it well in ‘Ill Fares The Land’ (2010), p.217-18:

“We in the West have lived through a long era cocooned in the illusion of indefinite economic improvement. But all that is now behind us. For the foreseeable future, we shall be deeply economically insecure. We are assuredly less confident of our collective purposes, our environmental well-being, and our personal safety at any time since WW2. We have no idea what our children inherit, but we can no longer delude ourselves into supposing that it must resemble our own.”

It’s time to reawaken the slumbering state and its decayed political class. It’s time to address the market disease of short-termism, weak supply chains, forgotten individuals, and a diminished national position. However, while awakening the state it’s important to take the lessons of neoliberalism: don’t let the state completely free. Figures like Harold Macmillan (Tory PM from 1956-’63) and Harold Wilson (Labour PM from 1964-’70 and ‘74-’76) were accused of using the state to generate unreliable growth at the cost of long-term public finances. Known then as ‘Stop-go’ economics, chancellors pumped budgets with spending and then subsequently cut budgets to control inflation. The overhanging debt and inflation fed into the 1970s crisis and left the country vulnerable to international shocks. Neoliberalism’s great strength was to generate growth and wealth without this inflation or excessive national debt. For this reason, our new state cannot spend its way to economic growth. The question becomes, then, how will the state help market productivity while retaining this neoliberal emphasis on efficiency?

As the overriding principle of the new consensus will be restoring economic productivity, the state must be a force within the international and national market, a passenger no longer. That means pushing our national market and USPs within the world system through economic rejuvenation.

Ideas on How to achieve this?

1. Catalyse the opportunity maximisers in the national market (Education, Research and Development, business incentives/restructuring for long-term investment – bringing the public and private together)

2. Control strategic parts of the national market (Taxes, nationalising strategic services when needed, strong capital investment)

3. Devolve the national power structures and market. (Regional inequality, underutilised individual, political and social cohesion)

Catalyse

The state must work in partnership with businesses to boost economic productivity. Too often corporations prioritise short-term profit over long-term productivity gain. On the flip side, the state becomes too disinterested in the economic sphere, allowing damaging regulations to build up, while national talent pools drain, preventing growth. The result is an economy that funnels wealth into the safer, already asset-rich individuals and companies, creating a drag on economic growth as saving rather than investment or innovation becomes the norm. An active state that seeks to encourage private investment in people and technology over pure wealth extraction would go a long way to redressing this issue.

In particular, this will be targeted at the key areas of strength for the UK economy. Utilising strengths in areas like research through collaboration with universities will factor into a state strategy based on catalysing market forces, rather than exerting as much overt control as pre-neoliberal governments did. This would also take advantage of the UK’s strength in soft power, rather than trying to compete in areas of weakness. The nation’s competitors include the US, EU and China – markets far larger and more powerful, so focusing on existing areas of strength will be a key part of a consensus striving for growth.

Along the same lines, state investment in public services – particularly the education system and community support – will help create a more productive economy through improved social capital. Not by hindering private profits to expand state control, but by driving private growth through investment in the existing public sphere. Collaboration with private capital will be key here, too, to ensure spending doesn’t balloon into higher borrowing — which would be highly costly given interest rate levels, electorally unpopular, and spook the markets (for any party – see Truss’ meltdown of a mini-budget).

The key to using the blunt options of the state is to be targeted and nimble. Targeted: investment in areas of strength and collaboration with strong institutions. Nimble: Not intruding into the market and in doing so warding off private investment. Both give and take.

Control

State control is frequently synonymous with nationalisation. Since the early-mid 20th century, much of state control has been exactly that – the NHS is the classic example. With the new tide’s expanding state, we are likely to see a return to a similar focus on state control, but significantly more reserved. Mass nationalisation a la Corbyn is unlikely given the electorate’s distaste for over-promising and the expense of increased borrowing (not to mention its debatable efficiency). Instead, more limited promises of strategic nationalisation in which the market cannot fix are likely – areas such as Social Care, housing or energy infrastructure. Though Labour is the likely option given its electoral prospects and ideological tendencies, either party could bring forward this style of pledge. Already, cross-party figures have called for a National Care Service, for example. Solving only the most salient public issues through intervention is unlikely to be challenged once it’s done, too, as any party doing so would be seen as reviving the problem – think of the Conservatives’ acceptance of social housing or healthcare after the 1940s.

This will be indicative of a wider state focus on flexibility and delivery, which will entail only intervention where practical and necessary – a key part of its cross-political nature, as this doesn’t stray too far from left or right tendencies. The UK’s successful vaccine procurement and rollout is a perfect example – led by Kate Bingham (expert in vaccines) and Emily Lawson (expert in delivery), this exemplifies the partnership between state and business that will define the new paradigm. State investment in private development of the vaccine, taking on the risk (which the market cannot do on such a large scale) before state capacity used in distribution.

To ensure the ‘controlling’ aspect of the consensus works, a new revitalised and reimagined state must be created to deliver – a new civil service. Recruitment must be more skills-focused — emotional as well as intellectual intelligence – and less contact or education dependent. A new Civil Service specialist university/training centre must be created to skill and reskill current civil servants – reducing the public-to-private churn. Departments and senior civil servants must stop playing court politics with each other. Growth and productivity – the crux of our new consensus – must be institutionalised into the key power bases of the state. Most important will be Treasury reform, the home of neoliberalism will undoubtedly be a drag on the new consensus. The norm of constantly moving Civil servants from post to post after 1-2 years must be abolished – keeping people in post for 5+ years will build institutional knowledge and focus on performance rather than ladder-climbing ranks and petty politics. Long-termism and the future must also be built into our new nimble state with its reinvigorated civil service – with forecasting and future planning key to national projects.

Overall, smaller more authoritative teams and units have been proven to work better than large bureaucratic departments. These teams and talented individuals get higher responsibility and thus risk. What this enables is a nimble and targeted state – focused on delivery and reform, not court politics or briefing to the media. Why? Because their legacies are on the line.

Devolve

The final piece of the puzzle will be devolution – for two reasons:

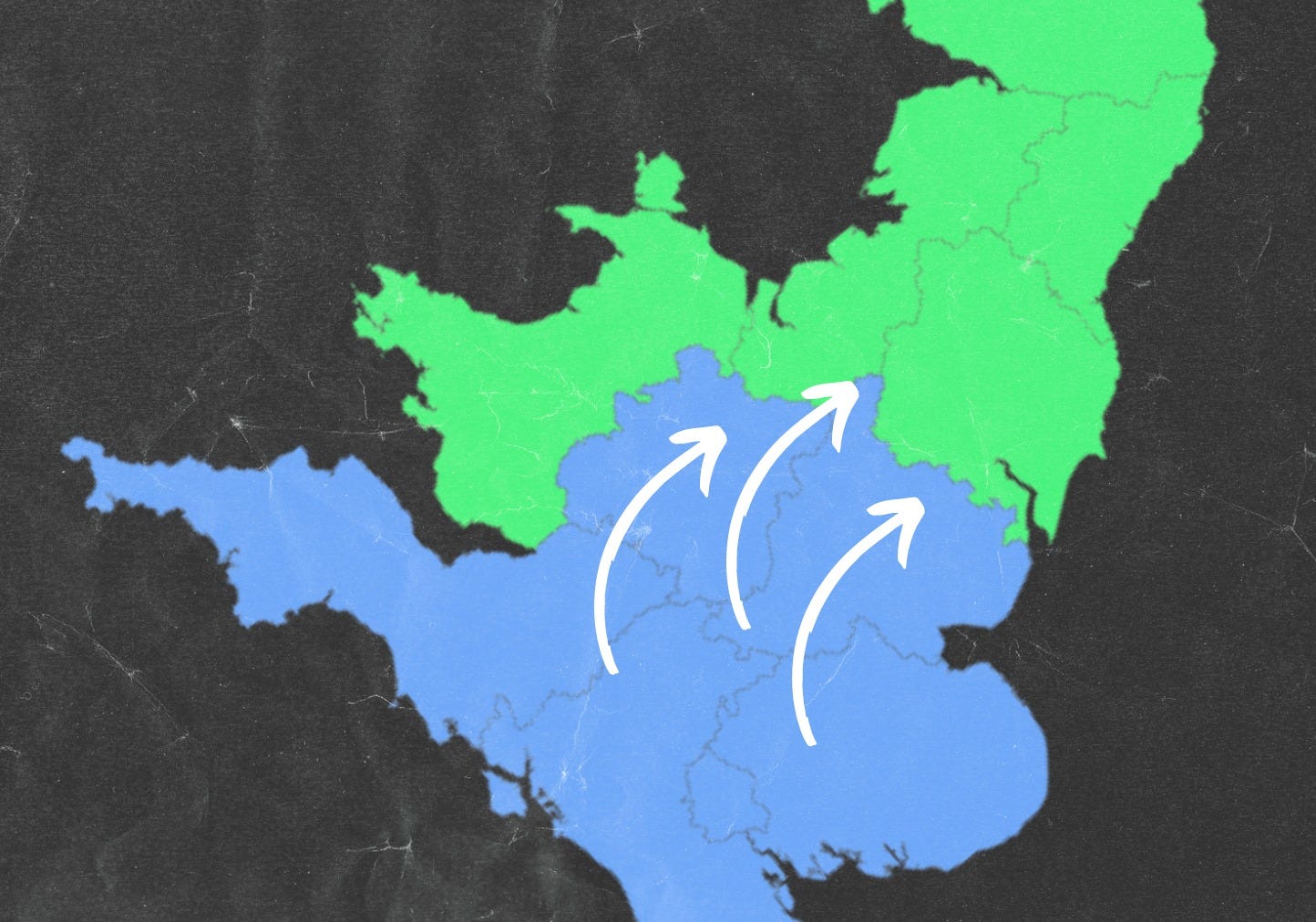

First, devolution addresses perhaps the underlying national issue: inequality. Neoliberalism naturally encourages inequality, but Margaret Thatcher’s policies of deindustrialisation meant that whole regions of the UK, especially in the North and Midlands, as well as parts of Scotland and Wales, have been structurally ‘left behind’, creating an economy worryingly reliant on the South East and London. Investment is badly needed in ‘left behind’ areas as a result, something that parties across the spectrum agree on – see Johnson’s levelling up and Labour’s long-term concern with inequality. Investment in declining public services, especially education, transport, and healthcare, via devolved government that knows what communities want and need better than Whitehall, will be a key aspect of redressing this flaw of neoliberalism – the success of Andy’s Burnham and Street are good examples of devolution’s benefits for these regions.

The deep power inequality between Westminster and the rest of the country will also be addressed – ensuring decision-making on a more efficient micro scale. Power should be a conversation and negotiation between a centralised state (Westminster) and decentralised regions/ cities, with both parties buying in. Having stakeholder buy-in creates a stronger imperative for growth and deals. We’re starting to see this in cross-party calls for devolution — not only has Labour announced their completed report recommending economic and political power redistribution to the regions, but prominent Conservatives like Adam Hawksbee and Ben Bradley have recently acknowledged the need for similarly radical devolution. Michael Gove has also been key to his party’s efforts in this area – his levelling up proposals included 30 new devolution settlements, for example (most recently in the North East). Jeremy Hunt is also deciding whether to devolve further tax and spend powers to Andy Burnham (Manchester) and Andy Street (West Midlands) soon.

Secondly, the best way to right the wrongs of an overpowerful state (Control) and a rampant market (Catalyse) is to create an inbuilt check. Devolution is just this – ensuring regional areas are having their say on what growth and progress look like. The unbridled YIMBY (yes, in my backyard) nature of the Wilson government with new towns has certainly created some weak infrastructure legacies and aesthetics, even if the building was desperately needed, generating a ‘bad’ image of what progress can look like. YIMBY politics will triumph over the NIMBY (not in my backyard) only with consent and cooperation. However, TPI predicts a wave of YIMBYism in deindustrialised areas keen to have industry and state investing back. It’s not a coincidence Blue Wall, more well-off constituencies tend to be NIMBY.

Conclusion

We are already seeing, therefore, the start of a shift towards a political consensus that seeks to redress the inefficiencies of the previous neoliberal tide, while acknowledging a small-c conservative electorate used to a small state. This new tide will likely be further left than neoliberalism (at least on national intervention), but further right than social democracy, having integrated some of the ideas of the former tide – a synthesis of Attlee and Thatcher’s theses. It will be defined by a state that does not purely rely on public spending for economic growth but encourages businesses to seek long-term productivity over short-term profit and devolves power to new forms of local government.

Devolution and investment will politically and economically empower these regions and prevent the brain drain towards London and the private sector. A state that will not rely on individuals to resolve social issues, but will properly fund public services and ameliorate inequality, both regional and otherwise, while always keeping an eye on the level of borrowing. In a Rawlsian sense of his ‘difference principle’: inequality should be to the benefit of wider society. This will only be done through a competent and powerful state – a political class willing to innovate and deliver. Risk taking must return as a key asset of the British Civil Service. Inertia is not a condition that creates growth. The new consensus could, however, be achieved by either party. Starmer’s reformed Labour seem the most likely candidates, but the Conservatives (or a different / new party) could move in the right direction. For now, there seems to be a fusion of the two previous tides of British politics into something new – but how exactly this manifests itself is still wide open.

Thank you for reading. A like, subscription or share goes a long way.

For feedback or to contact us, email at thepolinquiry@gmail.com