State of Play: The Mantle of Change

Purge and churn has corrupted the Conservative philosophy of change to conserve.

These pieces take time to research, write, edit and design. We greatly value any appreciation shown with a free subscription, like or share. Thank you.

“A state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation”

(Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France, 1790)

After a week in which the supposed party of socialism has undoubtedly assumed the title of heir to the throne, it seems only apt to return to Burke, a man no stranger to war, revolution and the politics of power. The ‘father’ of modern Conservatism in the British Tory party, Burke produced a compelling defence of an ideology which can sometimes, fairly or unfairly, be lost in a sea of negativity. Without Burke, you do not get the great Tory reformers of Robert Peel, Benjamin Disraeli or, even, the post-war centrists of Harold Macmillan or R.A Butler. The whole myth, which Disraeli partly invented, of the One Nation Tories was described by him as those ‘Tory men [with] Whig (liberal) measures’ (Coningsby, 1844). But for all Disraeli’s 19th century mythologising, the concept originated with Burke in the 18th century and his reflections on the 1789 French revolution – a time when Britain’s political stability became a defining differentiation against the revolutionary politics of the European continent, albeit aided by authoritarian measures of then prime minister Pitt the Younger. It was Burke’s idea that ‘a state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation’ that became the original foundation of the modern Conservative party, seen later in Peel and Disraeli’s reforms and then again throughout 20th century premierships. The joke is that Burke, who ‘founded’ this modern conservatism, was not even a Tory, but a Whig.

As I’ve written before, the very definition of conservatism is opaque – as is its implementation. The ‘ends’ of the British Conservative party is, if anything, to win power mostly because, as written in the last State of Play:

”It is the only ‘trusted’ outlet of conservatism – an ideology that favours the status quo rather than change, and thus conveniently its own continuation. [It is] A self-reinforcing idea from its original design.”

So why raise Burke? Well, over conference week – and one could conclude the last few years – Conservative government has been defined by strikingly ‘unconservative’ action. Or, more accurately, inaction in several areas, none so obvious as the abandoned 2019 Tory manifesto. This accusation of inertia, however, requires some nuance.

While the party favours cautious approach to governing it has been, in essence, Burkean – in other words it regularly changes, sometimes significantly, to conserve – whether in line with its traditional beliefs (property, family, nationhood etc) or as is required for electoral dominance. The aim of the strategy is to deliver minimal change in order to suppress the desire for further radical reform or even revolution. To achieve that conservatism the party has to slowly change the political-economic settlement in order to conserve stability and, thus, its own electoral power. But over the last period of government, the Conservative’s desire to enact this strategy has dissipated, with dramatically adverse effects for its electoral and philosophical future.

Who owns change?

However, rather than write another discourse on the conundrum of the ideological position of this party, which I did in the last SOP, this piece will focus on the actual ‘mantle of change’ within the British political system. In exploring who owns the idea of change you can quickly ascertain where Labour and the Conservatives are heading both electorally and ideologically. But before I start a quick note: yes, I know the word ‘change’ is very vague. However, it is useful as a concept / vibe, combining a mix of several feelings, whether a desire for new policy, new government, and new leaders, or just a simple knee-jerk, almost vengeful, desire to punish those in the current government.

To better understand this ‘change’, it is best to recite a key rule in British politics: young, incumbent governments, within our system, which have overseen a strong economy and made legislative progress don't tend to lose. The election these governments face is usually not a ‘change’ election but instead a ‘scorecard’ on their performance – essentially whether the electorate feels their grade warrants more or less power. It is rarely a question of their actual right to govern. The next election is certainly not a ‘scorecard’ election. This is because the economy is still very weak (the key driver of voting intention) and the Conservatives are no longer youthful but ageing after fourteen years of government: one ridden with crisis, failed / minimal reform and leadership churn. All of this suggests a 2024 Labour victory. As Johnson proved in 2019, this does not mean the end of Conservative hope. If Rishi Sunak could redefine himself against previous incumbents he could theoretically win as a change candidate against the toxic brands of Liz Truss or Boris Johnson. Therefore, grasping which party has the best claim to it is the best way to analyse conference week.

A Party of Change

Beginning with Keir Starmer and Labour, the internal transformation could not be clearer. Four years ago the expectation was another decade of Tory rule due to the margin of the 2019 victory. The Labour party was ruled by alleged anti-semites and divided by the toxicity of radical left-wing ideologies. After a fourth straight defeat Labour were, in effect, turning their guns on their own revolution. The Burkean Tory strategy of 2019 had, as it almost always has, sent the radicals packing.

Four years later and it seems we have entered a parallel universe. The party, led by a former Corbyn frontbencher, has transformed. From a strategic and policy perspective nearly everything was reformed. The suicidal strategies of targetting unwinnable seats in the hope of arch-Tory-capitalist scalps while failing to defend those true working class seats are gone. Also abandoned are the ideological divisions of utopia-nationalisations, the cacophonies of tax rises and the gleeful haemorrhaging of Liberal / centre-left voters. And, importantly, while policy and strategy was reversed from the heady days of Corbyn’s socialism, the party has retained, as noted in my two part series on crisis and ideology, a critical shift: that the government can do good, and in fact must do good. For Labour the state, in an age of crisis, is above all the enabler of change.

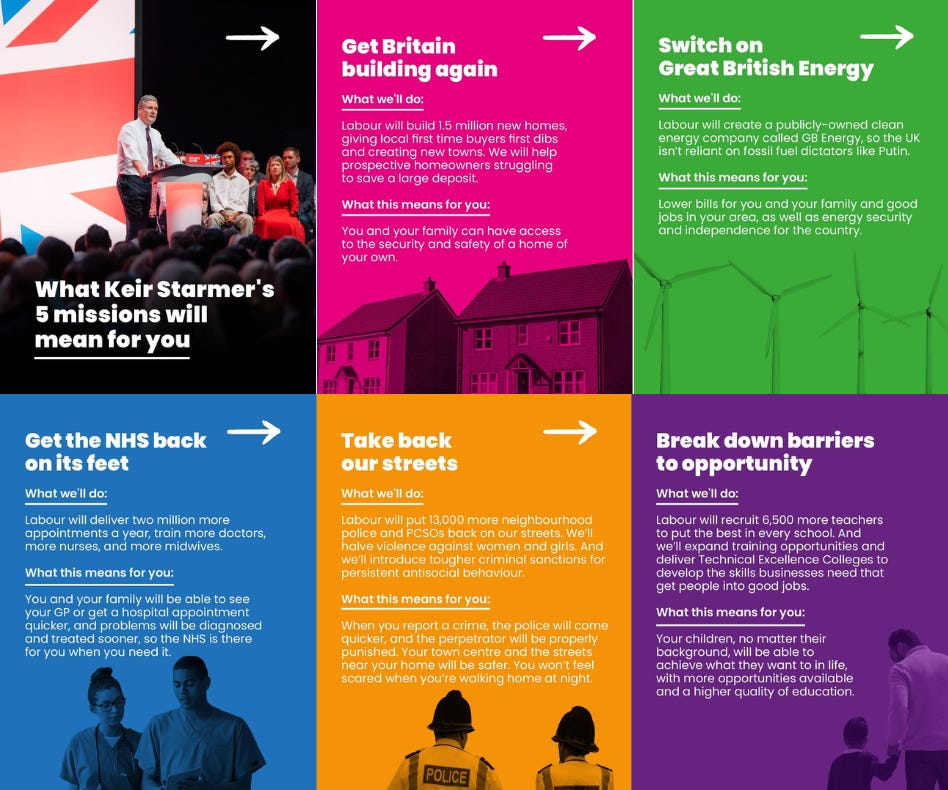

It is this story Starmer weaved into his conference performance, and he shone – sparkled if you like. The speech was, if not a dramatic announcement of new policy, a necessary polemical defence and promotion of the need to change and government's role in delivering it. From a Tory perspective Starmer's most disturbing development was his invasion of the housing battleground. Owning homes has, since Thatcher’s right to buy or Macmillan’s impressive house-building, been a Conservative default – property is, after all, one of those traditional values that creates a Conservative. But, after thirteen years of failed housing markets, fattened with the hay of low interests, Labour have taken the aggressive step to reclaim housing as their own. In doing so Starmer knows this is a risk – partly as it involves destroying the green belt and overriding local councils / residents on new builds. However, Starmer is in full pursuit for the mantle of change. Labour have realised that the policy of housing is not only morally right – one only has to look at Hastings for an example – but is a net gain electorally if it can energise the young, the renters and the ‘just on the ladder’ buyers. More importantly it can finally own the mantle of change – especially when combined with the bold pledge of energy nationalisation and other ‘mission’ policies of NHS renewal, education spending and crime crackdown. Crucially, it can avoid scaring off swing (and even core) voters by espousing reasonable, forward-looking change, which is targeted, achievable and highly relevant to the needs of the country.

If you want any further confirmation of the shift in the body politic, it is the right-wing elite's praise of Starmer who, it seems, has become the pseudo-Burkean figure British politics they secretly desire.

Lost in Flux

While the Labour conference was a culmination of months, in fact years, of incremental internal party (almost Burkean) reform, the Tory conference was the exact reverse. The party faces a strange conundrum: a leadership actively trying to win an election while a majority in the party – and significantly the key power factions – have given up and are instead focusing their time and political capital on the 2024 Conservative leadership race. The head of the snake, however, can't move without the body: the Conservatives are stranded, plagued by ideological division, factional ambition, and lacking a uniting force.

The complete capitulation of the party to even countenance governing is itself an explanation for its likely downfall. Rather than a “disposition to preserve and ability to improve”, since Brexit, the party has entered its own pointless internal revolutions with tragic implications for government. Purge and churn has replaced change to conserve, with five prime ministers and no throughline of reform or action. The final vague form of a strategy, noted by Tim Bale, of ‘Rishi or Bust’ is looking more and more like a bust (p.292, Conservative Party After Brexit). Sunak’s speech, itself not dire, contained promising announcements of smoking changes, education reform and different investments in the ‘Northern network’ of train infrastructure. What the speech revealed, however, was the very microcosm of Tory failure: promising change while failing to deliver. The ‘£36bn announcement’ of the northern network was later described as ‘illustrative’ and not ‘substantive’. In other words, a Johnsonian lie, akin to the ‘40 hospitals’ porky of 2019.

The other key issue is not just Sunak ruling over an ageing government but the upcoming 1-year anniversary of his. Many of these policies announced, while intriguing, have come after a year of government. If, as Sunak said, he wanted to be the ‘agent of change’ surely it should have come quicker? What Johnson did accomplish in his early premiership was quick signalling of change to the previous incumbent – just two months after getting into power, the 2019 Autumn spending review arguably ended austerity. If Sunak cannot achieve the low hanging fruit these reforms represent, in doing so differentiating himself to previous leaders, the ‘mantle of change’ will be an unattainable position to reach, and thus so will re-election.

Overall the conference was a sorry sight. Its retreat from actual meaning was epitomised by Penny Mordaunt’s speech – which simply repeated ‘stand up and fight’ 12 times without actually stating what it should fight for. Unlike in Burke’s time, there is no revolution next door to rally the troops against or destroy – Starmer is no Robbespiere, nor even a Thomas Paine. As noted at the start – the notion the party can simply win without the necessary legwork of partial change shows how infected the Conservative’s deeper philosophical origins have become.

However, the Tories are not just failing on the delivery of change, but are confused about what they should conserve. One only has to look at the rival factions to understand the division in the party: the most prominent being Suella Braverman’s post-ERG faction of the populist anti-immigration wing. Braverman’s backers are in opposition to Truss’ resurgent faction of ‘Growth’, essentially the radical neoliberals, responsible for the disaster last year, who actively support immigration for growth, but would like to cut most spending in government. The third, and ambiguous faction, is Johnson’s – supposedly pro-net zero, infrastructure (HS2) and regional levelling up – almost the opposite to Sunak. The winner of the next leadership will, evidently, be a game of thrones mixed with a game of radical ideas. The party has never entertained such a toxic mix of personal ambition and ideological division. The result could be years of opposition as the mantle of change shifts to Labour.

Fundamental Shifts

I admit the two concepts tackled in this piece are a bit different: the mantle of change certainly does not mean Burkean change. You can have much more radical change which still wins elections – for Labour, Attlee in 1945, and, while less common for the Conservatives, Thatcher’s neoliberal shift is a notable example of this. For now, though, Starmer has clinched the mantle of change and is on his way to power – the question for him is whether he can maintain it over twelve months. If the shift in social attitudes, as well as recent by-election results are to be believed, it seems they will.

But the reason that I have intersected the two changes in this analysis is not just because Labour have achieved a reputation for reasonable change. It is a more striking phenomenon than that: the Conservatives have surrendered their Burkean strategy, and philosophy, without replacing it. While the party still aims for some sort of ‘change’ it is completely unclear what that change should be and thus what it should conserve. Is it a Braverman anti-immigration populist party? Or is it a Trussite pro-immigration neoliberal fantasy? Or does it prefer the fairytale of Johnsonian intervention? Or, simply, will it revert to Sunak’s ambiguous anti-interventionism? There is no governing definition, nor evidence for their ability to enact it. It is for this reason that the retreat from their philosophical origins has relinquished the Conservative’s claim to power. Purge and churn, as well as the lack of delivery over fourteen years has killed the party’s raison d'etre. Change to conserve has been replaced by the new duality of personal ambition and ideological division. It is a vicious cycle the party must escape if it wants to win again.

If you enjoyed the piece, a free subscription, like and share goes a long way. Thank you.

Tom Egerton is a political writer and researcher, his upcoming book ‘The Impossible Office: the history of the prime minister’ is out in February 2024, published by CUP and co-authored with Anthony Seldon. Follow him on X / Twitter here.