State of Play: Dealing with Inheritance

The challenges and opportunities of Labour's first major governing decision

If you have enjoyed the reading The Political Inquiry we would appreciate anything you can give back with a free or paid subscription. All donations received will be put back into the Substack to continue its development. Thank you to those who have already subscribed and donated.

It's been over eight months since my last State of Play, a series which investigates political strategy and narrative, separating superficial churn from real political developments. The last piece was written immediately after the 2023 conferences, at which time it became evidently clear Labour were on course for government with Rishi Sunak’s umpteenth relaunch having disintegrated on impact. For the remainder of 2023 and most of 2024 there were no serious political transformations – just froth with little discernible strength. Many, including me, thought we would see a year of inertia, with an election called in October / November 2024. It seemed this series was set for a year-long hibernation. But even I underrated Sunak, calling a snap election on what we still believe was a snippet of inflation data and losing so badly it compares to nothing since the 1832 Great Reform Act. That's almost 200 years of British politics – and 100 years of full democracy.

But Sunak was the future once – the party now faces years of slogging through irrelevance and opposition mud. Conversely, the ascendent Labour have enjoyed a successful first few weeks, overall a well crafted entrance into office. Keir Starmer has discovered a deft, if nascent, prime ministerial tone – the most impressive since David Cameron or Tony Blair. But Starmer will need more than soothing tones to overcome the constraints of government and international politics. The primary task, for now, is dealing with the party’s economic inheritance and utilising the opportunities it creates.

Inheritance of History

Most post-war Labour leaders have inherited a Britain in a pretty shoddy state. Clement Attlee’s 1945 saw a Britain destroyed by war, diminishing in economic and geopolitical power but desperate for fundamental social-political renewal. In that time of visceral pain he utilised a hard inheritance to rebuild Britain with a new social democratic foundation, and with Ernest Bevin began to reimagine the security of Europe and the Empire.

Harold Wilson’s ‘thirteen wasted years’ remark about the Tory premierships of 1951-64 was a clever device. The Tories left a large deficit and the economy lacking in innovation. This offered the opportunity for Wilson to reinvent the state and follow Attlee’s aims of creating a nation more self-sufficient and less subservient to the market or balance of payments.

James Callaghan’s inheritance in 1976 was one of the worst, but using the IMF crisis and dreadful economic situation he weaned Sterling away from reserve currency status and brought a more stable pay-agreement with the unions. Douglas Jay later remarked it was the only Western government between 1977-79 to reduce inflation and unemployment successfully – only failing in his later 5% pay rate.

Tony Blair’s 1997 economic inheritance was probably the best of all Labour prime ministers. Between 1992 and 2008, he and John Major oversaw 16 years of successive economic growth – the only issue being the entrenched market structures (in both the electorate and economy) acting as a block for social democratic change. This didn’t bother him much, and he instead focused on fixing the Tory inheritance of damaged public services – their brilliant recovery easily became the strongest element of his record.

Gordon Brown’s inheritance again was quite benign, though after the dominant Blair decade the scope and political capital for renewal was limited. It required a bold and risky strategy based on reconnecting with the electorate and reinventing New Labour – his failure to call the 2007 election ended his hopes. But, the handling of the 2008 financial crisis, regardless of Labour’s acquiescence to the City, again shows a PM’s ability to achieve during a crisis.

Labour Now

Labour’s inheritance is astonishingly bad – slightly better than 1945, but almost level with 1976. The analysis of Paul Johnson, director of the IFS, from my recent book reads as a toxic top hits list: real GDP per capita £11,000 behind the pre-2008 trends, stagnant real wages (still at £450 a week as in 2010), investment as a percentage of GDP never reaching above 20% (compared to the consistent mid 20s for the US and EU), business investment uniquely stagnant since Brexit, debt as a percentage of GDP reached 99.5%, the 2010-19 period saw the biggest and most sustained cuts since WW2, while over the 2019-24 parliament tax levels were increased to to the highest since 1945. Productivity is 13% less than Germany and 8% less than France – floating at a meagre 0.4% per annum average increase. To top matters off, 2019-24 was the first parliament in modern history to record an overall decrease in living standards, with a 0.9% decrease in real household disposable income. With all that, inflation remains an underlying worry after its 10% peak in October 2022 (particularly because of the escalation in the Middle East) while interest rates are stubbornly high over 5% – and Gilts are hovering around 3.5-4%.

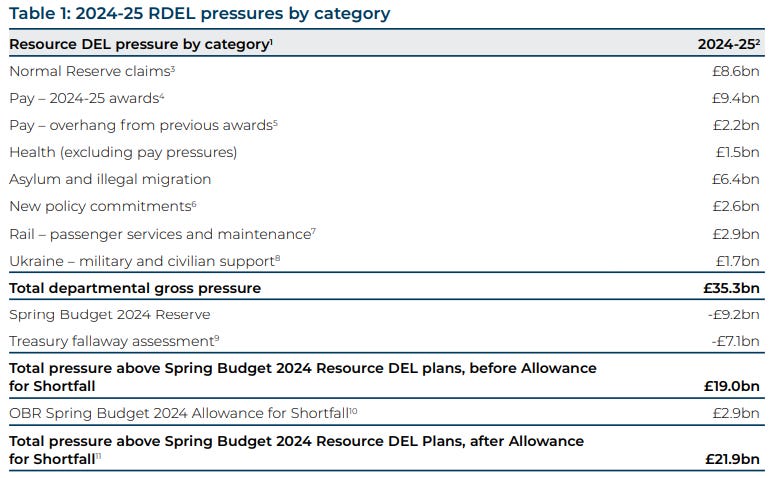

In response to this inheritance, Rachel Reeves is pursuing an somewhat effective framing strategy. First Reeves has ensured all of the Tory’s hidden bombs are displayed to the public at full scale. It's a testament to late Tory governance that these problems span not just the core economy but key infrastructure: prisons, courts, water, rail, unions, health, local government, education, and other public services. Simply put, these problems need a lot of money to fix. This political framing of Tory failure is a pivotal precondition for the Labour government – the narrative must be as strong as Cameron-Osborne 2008-10 which gave them remarkable room to implement, and form a consensus around, austerity. If successful it will give Labour political cover for innovative (but politically difficult) revenue raisers, or to make tricky departmental decisions (such as releasing prisoners early). The Office for Budget Responsibility’s Richard Hughes’ damning letter on the £21.9bn Tory departmental overspending especially an astonishing £6.4bn on Asylum, is both a final verdict on the last few years but also deeply ironic that the OBR, which George Osborne setup to enshrine Tory-fiscal prudence into the state, felt so compelled to send a parting shot at its political creators. It’s an indictment that will reverberate through the next five years of Tory politics.

Tom Hamilton summarised the situation well on his

In 2024 people voted against the Conservatives in huge numbers, and for Labour in admittedly much less huge numbers but substantially huger numbers than they voted for the Conservatives, because they thought that the economy was crap and they thought public services were crap. That’s bad news for the Conservatives’ attempts to define their legacy, but it isn’t great news for Labour either, because now it’s their job to rebuild crap public services with a crap economy.

For Labour the historical lessons trigger questions over action and speed. On action, many within the government are scared of repeating Wilson’s mistake of doing too much micro before the macro is solid – he failed to accept the wider economic atmosphere, tirelessly pushing his economic reforms which crumbled in the face of global markets and deflation due to an overvalued pound. The second is speed: move too fast and one could alienate the markets and country, as seen with Truss, which is why many praise Thatcher’s first three years (1979-82) of strategic tiptoeing before strident reforms were implemented after the 1983 election. However, this logic ignores the immediate need for political reform and that Labour have the most political capital they are ever likely to have during this period in office (due to the mandate and recency-bias of the last 14 years). They must, therefore, act decisively while maintaining a balance.

Next Steps

One modicum of good news for Labour is the first interest rate cut announced by the Bank of England, from 5.25 to 5% – though the knife-edge vote and hawkish tone elicits the worries of inflationary pressures remaining in the domestic and global economy. This black hole is also separate to the IFS’ £20bn parliament-long black hole it illustrated during the election. But while it is right to note the pain in monetary conditions and public finances, there is some obvious creative accounting in order to build the political narrative for a larger state. I’d say of the £21.9bn black hole, at least £6bn is dubious – so is the amount of departmental reserves being used (an unknown quantity of the £8.6bn).

The difficult choices, such as means-testing / cutting the Winter fuel allowance, could be seen as required, but the cuts in social care and departmental budget (inevitably translating to a decrease in vital capital spending projects such as the £1.3bn fund on tech and AI just cut) starts to pose a serious question: if Reeves has constructed such a brilliant political narrative, why is it not being utilised to implement innovative revenue raising, rather than traditional cuts? A degree of consolidation is understandable, especially if these department spreadsheets are as messy as they seem, but social care and capital spending are some of the worst areas to focus on – though they are admittedly the easiest in terms of size to cut.

However, the ‘black hole' political narrative matters most in the short-term set up of the budget. The early signs are that one could expect about £10bn of tax rises, £7bn in extra borrowing and the £5bn announced in spending cuts. This together will see off any departmental blackhole. But the deeper question is could Reeves go further? There are intriguing noises that the fiscal rules on debt, something that is screaming out for reform, might be reformed – slightly contrary to what Reeves was saying a few months ago. Even minimal changes to how we finance debt and borrow could unlock, on a conservative estimate, about £10-15bn. This is before looking at more radical accounting changes or politically challenging tax rises – whether wealth or otherwise.

As I’ve written before, I think the fact that Reeves is keeping the scheduled National Insurance cuts is a long-term electoral decision by Labour: putting more strain on household income after the cost of living crisis is anathema to them. However, it could also be interpreted as ideological, as we mused in the election, of a broader desired shift of the tax base away from the worker (in both direct and indirect taxation) and towards capital / wealth. The challenge Reeves faces is she needs to stimulate growth – which at the moment comes from the City and big business – and thus can’t spook them too much nor eat too much into their regulatory competitiveness. Once growth returns, more radical investment and economic strategy can be introduced to start changing these fundamentals. For now, it seems impossible to do much.

Budgeting the future

For the first budget, one Labour thought they wouldn’t even get, the ‘fixing the foundation’ narrative will work – it is a clever political strategy representing some of the reality of Tory inheritance and laying the groundwork for a large state. The opportunities of the terrible inheritance have enabled Labour to rewrite the political narrative – and possibly the sketches of a new consensus. One cannot blame Reeves too much for initial caution – particularly with the upcoming US election, global stock market sell-off and Middle East conflict. But if macroeconomic conditions continue to improve into 2025/6, as hinted at by the interest rate cut, Reeves must not shy away from the inspiration and promises of the movement she represents. If Reeves does, she could become the nemesis of the spending departments, and Starmer, very quickly.

Tom Egerton is a political writer and researcher, his new book The Conservative Effect, co-edited with Anthony Seldon and published by Cambridge is OUT NOW, you can order it here: with Cambridge, Waterstones or Amazon. Follow Tom on X / Twitter here.

“Laying the groundwork for a large state” would be strikingly at odds with Starmer’s promise of a government which “tread[s] more lightly on your lives”.