In the midst of battles, soldiers encounter the fog of war, but there is a more general phenomenon in politics, the fog of events, which makes it hard to grasp the significance of what is taking place, to distinguish the really important from the merely ephemeral, so overloaded are the airwaves with every possible interpretation.

Andrew Gamble, 2009.

By many accounts, Rachel Reeves is spinning around in a political-economic doom loop: trapped in a low-growth Britain, weakened by tariffs from the White House and weighed down by the stringency of her fiscal rules. On the face of it these factors seem the obvious danger to Labour's hopes for rejuvenation and re-election. But the roots of this supposed doom loop lie in the bureaucratic maze which modern Chancellors and Prime Ministers have struggled to overcome.

With that said, everything always looks worse in the moment – and a quick logical diagnosis (such as the ‘doom loop’ line) can very quickly become expected reality. What's actually happening from budget to budget is less discernible at the time. The foam of the wave can be mistaken for a very different force that drives it underneath. For all we know, minimal but stabilizing growth could return, the bond markets could stabilize and the external shocks – Trump Tariffs or otherwise – could be worked out with a minimal trade deal. Or, whenever you are reading this, Reeves’ headroom may have already been breached and the UK could be entering a wholly changed global scenario – with dire implications for growth. In either scenario the Chancellor would do well to redefine and repoliticize parts of Britain's economic strategy to shield Britain against this new world.

What the monetary policy is that!

Since 2008 it's hard to argue that Britain's growth model has been working at all. Between 2008-25 the country has experienced anaemic growth, domestic political instability and external crises. Historically, escaping decade-long crises require monetary as well as fiscal innovation. While Britain's monetary innovation of Quantitative Easing ensured safety in recent crises, it has saddled the Bank of England with £665bn worth of debt. Quantitative Tightening – the opposite of easing – is the unwinding of this debt.

Unnoticed by many is the pressure this has put on post-2022 Chancellors, with the Treasury forced to pay the interest difference (3% due to floating rates) to the tune of £18-36bn a year depending on the bonds. We have yet to see any serious innovation around this, although Reeves’s changes to fiscal rules to only account for interest rate losses was an improvement. The only source of dramatic thinking on this remains, surprisingly, Reform’s 2024 manifesto which vowed to stop paying interest on QE debt – similar to the New Economics Foundation push for a tiered reserve system.

Reeves' Autumn Budget seemed to destabilize the bond market in a number of ways. But a Latin phrase comes to mind: post hoc, ergo propter hoc ('after this, therefore because of this'). There were global factors at play. While there have been fewer QT gilt sales this financial year, they continue to put pressure on bonds – particularly with the government’s economic inheritance and borrowing aims. But there is also a lack of appetite to buy UK debt – a mix of many factors including the Trussite hangover and a continuing anti-Labour fear / mood of markets. The cost of borrowing is only increased by the short-term refinancing debt in a high-interest atmosphere. With the Trump Tariffs, UK bond demand will likely increase – but only for the wrong reasons.

Britain, therefore, is stuck in a very strange, and historically new, monetary position. Not only is it trying to offload lots of QE debt, it is doing this at a time of high interest rates, as the economy teeters on recession and global markets wobble in the face of Trump tariffs. This is even before considering the government's aims of borrowing to invest. The BoE’s downsides to cutting rates, even with tariffs posing an inflationary threat, is likely low due to the weakness of the market. The doves on the MPC make the case better than I could. It is also beyond belief why (fiscal) policy is still based on the OBR’s forecast of QT over the next five years! Meanwhile, continuing to calculate this forecast by just extrapolating the first two-year average is astonishing. This, basically, cuts into headroom – alongside the natural pressures of QT, current economic instability and high interest rates. The intentional HMT-OBR-BoE disconnect is damaging the government and the economy.

Political Choices

Monetary and fiscal innovation is lacking. The difficult but necessary reforms have, so far, been avoided. It may seem overly risky to attempt structural reform at such a moment – especially for a left-leaning government in market-dominated systems with the memory of October 2022. But anything worth doing in government is essentially hard and slightly risky, and Reeves has, so far, done little to help herself. Not only did she over-prioritise the OBR on her entrance into government, but the expectations set by Labour on VAT, National Insurance and Income Tax were short-sighted. While No.10 was busy with infighting for the first few months, No.11 orthodoxy persisted.

It's worth noting, however, that the Chancellor’s position has been systemically weakened since the 1997 privatisation of the Bank of England. Without the power over interest rates and forecasting (a very dubious art), the Chancellor must be much more strategic. However, this powerlessness should fuel a desire to be more creative. One of Kit Haukeland and I’s historical icebergs which Labour governments tend to hit, as seen in 1920s with Ramsay MacDonald, is that rather than act, Labour cower under self-imposed market rules and schemes that will supposedly return growth. This is not to say Labour shouldn’t be pro-market or strategic – but that being disabled from confronting the trade-offs of reform because of economic conditions in markets will likely prolong the problems, not fix them. No.10 and 11 thus need to coalesce on a more radical (not necessarily ideological) redefinition of the economy, encompassing root and branch fiscal and monetary realms. For now, Andy Haldane remains the best candidate to start implementing an in-the-round growth model rethink.

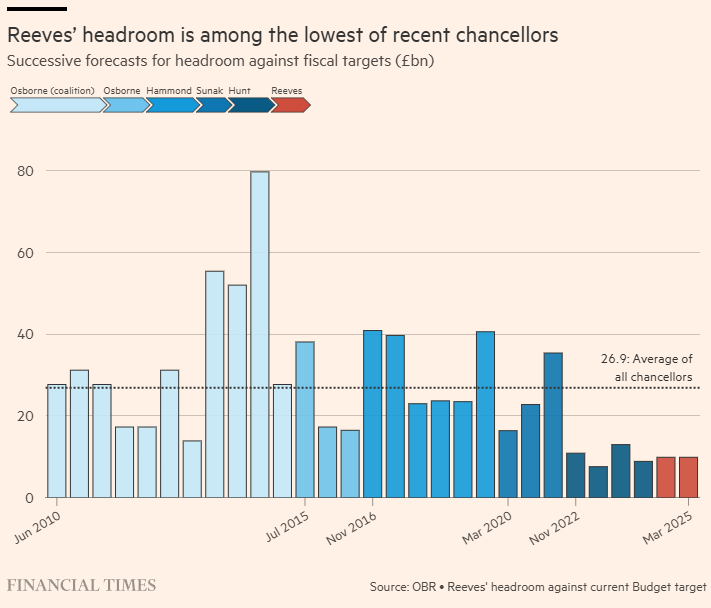

The OBR is one place to start. Created by George Osborne, it has thus far helped to bring down one PM (Truss). If these woes continue Osbrone’s creation could do as well as Boris Johnson in destroying a Chancellor and a second PM. As Chris Giles has argued (and also Will Hutton), there is very little accuracy and democratic legitimacy behind the mere fifty-two people that decide the forecasts. Without reform, Reeves faces yet more unpalatable tax rises in an effort to meet the OBR’s forecasts in Autumn as her headroom is likely to disappear – requiring just a 0.5+ increase in Gilts to wipe it out. The choices of further spending cuts or tax increases not only hurts the economic picture but will eventually destroy her position within the Parliamentary Labour Party and Cabinet. There is only so long Reeves can escape outright rebellion.

Thinking Backwards

All this feels very reminiscent of Harold Wilson’s first Labour government (1964-70) in which he attempted to fight the monetary facts of life in resisting a devaluation of the pound by attempting to re-establish its value through growth. The Department of Economic Affairs, national growth plans and national investment all came to little. What he didn’t realise, or refused to admit, was that keeping Sterling so high destroyed the competitiveness of industry and thus his growth chances.

It's too soon to tell if Reeves will mirror this path, but it seems Labour is once again making the mistake of fighting the fundamentals with timid ideas for growth. The Oxford-Cambridge corridor or Manchester United’s new stadium – along with AI plans, infrastructure and capital spending – are good. Defence spending and industry also offers a route – if again, borrowing and European-bank dependent. But they are just that – good, and don’t yet seem dial-shifting. The monetary beast must also be tackled, otherwise Reeves may be blamed for Labour’s unravelling economic position as Chancellor Jim Callaghan was in 1967.

The BoE – untouched due to depoliticisation – requires attention, its mandate should be shifted to something more akin to the FED’s targets for employment (beyond mere price stability). Another reform could be reinvigorating the Monetary Policy Committee’s membership with even more outsiders in order to stimulate creativity and debate. Or, simply, replace Andrew Bailey who has had an utterly unconvincing reign over the BoE – and a disappointing alternative timeline to what Haldane may have achieved if Dominic Cummings had got his way over Sajid Javid. Other important growth model-shifts need to include a spatial rebalancing of the economy. In the 19th century these came in the form of localised stock exchanges and Bank of England franchises based around industrial cities and hubs. London was not the only growth engine.

Luckily for Reeves, the pro-growth political infrastructure continues to grow in SW1. Notably there has been a shift towards a YIMBY and ‘abundance’ intervention agenda, with think tanks and groups springing up to support it. This stretches from right-coded / supply side Works In Progress, to the politically ambiguous Looking For Growth group (which I wrote about here), all the way to left-leaning / No.10-influencing groups such as the newly created Centre for British Progress. Labour Together and Tony Blair Institute also have many in government working on this; Tom Westgrath (from TxP / TBI) is one of the most significant new-wave thinkers, who was seconded to the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. Several of these groups have the backing of the Labour Growth Group led by Chris Curtis, which has the support of around 100 Labour MPs. The political ecosystem to support new ideas and people required to shift Britain’s growth model and rediscover economic progress is here. Without at least listening to their ideas, and with nothing on QT, the bond pressure and growth pain loop may be too much to overcome.

Autumn Beckons

To escape Callaghan’s fate, Reeves will hope for a miracle across the pond, a relaxed bond market, lower interest rates and a return to growth through the government's supply-reforms and spending. This is obviously possible. But if it doesn’t happen, and the geoeconomic / geopolitical position continues to worsen in the fog of events, Reeves’ fiscal rules may succumb to an increasingly blood-thirsty bond market. In this version of events the Chancellor would end up like Callaghan with her version of Sterling devaluation becoming a (possibly) unsurvivable fiscal rule change, or worse, persistent austerity. To escape this Reeves will need to innovate. Otherwise, not only would the 2029 election become difficult to win – but it's unlikely Reeves would ever recover like Callaghan to hold every great office of state and become Prime Minister.

Tom Egerton is a political writer and researcher, his next book is on the breakup of the Tory party in government - for anyone willing to chat please DM him. His latest book, The Conservative Effect: 14 Wasted Years? (CUP) can be ordered here: with Cambridge, Waterstones or Amazon. Follow Tom on X / Twitter here.