Notes on Electoral Economy (REDUX)

Notes on Electoral Economy

The following is a REDUX piece collating unconnected thoughts on how the economy intertwines with elections. The new version was re-published on 30/12/2023.

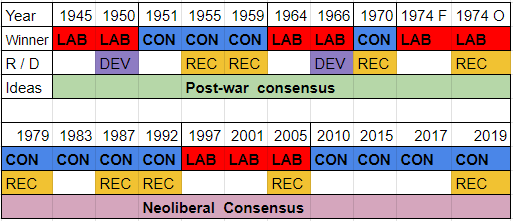

The simple post-1945 electoral cycle in Westminster elections:

The basic electoral cycle of winners since 1945.

The economic electoral cycle is an overlooked theory in modern day politics which can offer useful explanations for recent political shocks. The theory contends that governments rise and fall based on largely predetermined cycles of economic conditions, targeting and perceived performance. At its heart, the theory argues that governments have sell-by-dates which they struggle to outlast. To simplify the task, and best observe this theory, the following thoughts will focus on post-war developments.

Macroeconomic Conditions

Outweighing all economic factors, and possibly every other element of the electoral cycle, is the macroeconomic conditions surrounding elections and government. Shown in the depiction of the cycle (below), when recessions (REC) and devaluations of Sterling (DEV) are overlayed onto elections, they almost always interact with changes in government — known in academia as the ‘business cycle’ theory. This theory argues that political power is completely intertwined with the market and its economic impacts on the country. Evident not just on an institutional but also on an individual level, with the rise of a voters’ interaction with finance and economics — from student loans, tax receipts, credit cards, ISAs, to Blair money, furlough, universal credit, pensions and everything in between. These basic interactions have increased the overall salience of economic factors and how they impact a voter’s life. Since the rise of neoliberalism, this trend, sometimes labelled ‘financialisation’ has only increased.

The chart shows the recessions (REC) and devaluations (DEV), which significantly hurt the UK economy and influenced voting behaviour dramatically.

Each recession / devaluation occurred each period between elections — I.E after the 2005 election (2005-2010), the country encountered a recession in 2008-9 under Gordon Brown. The example of the Brown government is useful in demonstrating the business cycle theory. Even though Brown, arguably, handled the recession well (especially on a global scale), he lost power in 2010 because his record of economic competency was ruined. Taking the blame of an economic collapse destroys a government’s perceived economic competency, and thus ability to win elections.

This is exactly why huge economic downturns matter politically. Not only will individuals and families be squeezed economically (unemployment, no growth, inflation, interest rates, austerity etc), but it will trigger voters to search for an escape, and in the modern day the state is the provider of relief. Since 1945, government intervention has been pivotal in helping or destroying lives, and even in a world of globalisation the nation-state is still the UK voters’ most trusted and accessible lifeline, while also being their easiest outlet of anger. Multi-national corporations such as Amazon or Netflix, and global individuals like Bezos or Musk are not useful allies in trying to improve your economic / social conditions, even if they may have state-like power in the world economy.

So, the desire for those burnt during times of economic downturn to find an economic lifeline, and the resultant anger generated, is why macroeconomic factors are vital to voting behaviour. In 1979 Margaret Thatcher successfully pinned the blame of economic woes on Labour and the unions, regardless of Labour’s improved performance on the economy since 1976 (and the fact that Thatcher, not Jim Callaghan, oversaw more days lost to strikes in 1979). In 1997, Major was destroyed for his ‘22 tax rises’ and catastrophic ERM decision resulting in ‘Black Wednesday’ recession in 1993; even though by 1997 the economy was had recovered strongly — a gift for New Labour’s 1997-2010 administration.

The evidence, and corresponding theory, suggests it’s very difficult for a government to escape electoral pain if the economy collapses under their reign, regardless of culpability. However, there are exceptions to the economic cycle theory. The first is the 1979-81 recessions, triggered by a plethora of economic causes, though inexorably linked to Thatcher’s new policy of reduced economic intervention and desire to reduce inflation by increasing interest rates, both throttling growth. Due to five years of previous Labour rule, Thatcher was able to construct a successful narrative that assigned the causes of the recession on Labour and the unions. The economic narrative of ‘medicine’ Thatcher wanted to deliver was painful, but according to her, necessary. It’s undeniable, however, that it took a degree of luck with the 1982 Falklands war, which eventually enabled her re-election. The other note is also in 1987, when the stock market bubble burst, crashing 22% in one day and causing a recession. After five years of uncorrected growth, it was bound to occur. The fact that the market had risen 47% in previous months, and that it occurred after the 1987 election, explains its lack of impact on the UK political system.

The top line shows the elections held under the supposed political consensus.

The accepted wisdom that elections are fought on is also important as it can determine elite opinion, media coverage and general acceptance of certain economic policy. As seen above, from 1945-1979, Keynesian economics was somewhat accepted as the conventional position, and from 1979-2019 it was a neoliberal strategy that was dominant. Moving outside the realm of what’s considered the economic consensus of the day can have catastrophic electoral consequences. The media and markets may turn against the party, as well as the general public. Voters, according to consensus / cycle theory, favour stability over innovation. Foot in 1983 and Corbyn in 2019, or Truss in government experienced these hard truths when moving against the economic trends with radical policy.

It takes a once-in-a-generation PM to withstand economic collapse or forge / survive a new economic consensus.

Pre-Election Economic Policy

Commonly, politics is interlinked with this economic cycle theory, when politicians align economic decisions with elections in order to gain or remain in power. The quick lever for a government to pull is the pre-election budgets, where governments can pledge spending increases, or tax cuts, in order to win over voters before elections. This is essentially grounded in the idea that voters chose parties based on their economic position or their economic preferences for how society should look. The question government’s face is who should be (and by how much) rewarded before an election?

A key measure of a government’s popularity going into an election is how much they decide to ‘gift’ the public. If a government is in a weak position, expect large economic gifts. If it’s feeling strong, like in 2001, expect a more long-term budget designed to setup the economy and not play short-term politics. Political gifts can come in the form of tax cuts (Income Tax, National insurance, VAT, Corporation or tax allowance / thresholds). Spending is another form of the electoral gift, especially when spent on sacred UK institutions such as the NHS. Tax cuts are forms of spending, but are naturally smaller-state orientated as they enhance the individual and minimise the state by reducing future tax receipts. Spending is the opposite: nourishing the state with spending resulting in a more collective benefit for the public, and increased necessary funding mechanisms.

It’s important to note that economic policy is, usually, specifically targeted to a government’s key voter group (coalition), general ideology / policy, or in response to macro-economic conditions. Osbourne’s 2015 pre-election budget increased tax allowance by £200, cut taxes for middle / upper earners (£1000 rise on 40p threshold), loosened rules on pension savings, introduced new savings (investing) allowance and cut taxes for North Sea oil. It wasn’t exactly the biggest ‘giveaway’ budget, but reflected the Tories inherent belief in their ideology and strategy: help the middle / upper classes, business and older voters by keeping the economy stable through small government. Low inflation, falling debt and growth enabled this somewhat successful electoral strategy.

Electoral strategy (and thus electoral cycle) can usually override the government’s e desire for long-term economic stability. An example of this is in 1959 when Macmillan and Butler presented a very inflationary budget in order to achieve electoral victory after a period of austerity. It resulted in a majority of 100. The next five budgets (1960-64) were a mix of inflationary (spending) and deflationary (cutting) budgets designed to win voters in election years by pumping the economy with stimulus, while cutting that spending in non-election years in order to save the economy from inflation. This became colloquially known as ‘Stop-go’ politics, resulting in Labour inheriting a £800m deficit in 1964 after thirteen years of Tory rule.

Wilson (Left) and Callaghan (Right) were both blamed by the ‘New right’ for the economic crisis of the 1970s. What followed was the formation of a new economic consensus under Thatcher, later confirmed under Major and Blair.

The same can be seen in the Wilson government, when then Chancellor Jenkins entertained a mix of deflationary budgets in 1968 and 1970, while paradoxically allowing inflation and pay increases (demanded by unions) to run ‘hot’. It was the continuation of a strategy designed to let everyone feel they have money before the election, and dealing with the consequences afterwards. For those who know the political history of the 1970s, the consequences of this style of economics were not ‘dealt’ with. Irresponsible pre-election budgets led to the invention of the political theories of ‘democratic overload’ by King (1975) and Rose (1980), arguing that parties focused on the political gain of economic policy, and not stable economics, in order to win power. However, the theory falls down in failing to incorporate short term politics that weren’t purely economic. The recent examples being Cameron’s 2014 referendum decision resulting in his 2016 resignation, and additionally Johnson’s 2019 Brexit, which won the 2015 and 2019 elections for the Conservatives at the cost of the economy and party.

This strand of over-intervention fuelled by the voters and irresponsible economic policy was prevalent in the rise of the ‘New-right’ in the 1970s / 80s, with thinkers such as Hayek, Friedman and Rand, supplemented by thinktanks like the IEA or CPS, all writing on the breakdown of the supposed post-war consensus and destruction of the economy due to government spending. What occurred was a revolution in politics and economics through Thatcherism, and the beginning of a new economic-electoral basis called neoliberalism. However, even as the economic battleground changed, the tool of the pre-election budget continued with tax cuts in Lawson’s 1987 and Lamont’s 1992 budgets.

What’s important to realise is that politics and economics are never separate, and this is even more significant when considering the theory of the economic electoral cycle.

Microeconomic influence

The following is an incomplete exploration into micro-economic influence on local electoral shifts. Essentially it relates to the innerworkings of individual microeconomies within specific swing seats that determine elections (or electoral geography). Recently, journalism has simplified this to a ‘left behind Red Wall’, a set of local economies and individuals struggling for investment after their post-industrial boom and the rise of neoliberalism. Some have suggested this is a fallacy.

Historically, and especially under the supposed ‘post-war consensus’, economic voting behaviour could reasonably be ascertained through the classic social / economic class separation of ‘ABC1C2DE’. However, ever since the rise of individualism, and resurgence of nationalism / regionalism, it’s become harder to use. For example, Johnson won every single category of social class in the recent 2019 election. The general predictable divider of the present day is level of education, not necessarily just economic position. But education and economic position are inevitably linked, due to the price of university and superiority of private over comprehensive schools. So individual economic background is still vital in determining a voter’s politics.

The political microeconomics of job distribution, income, commuters, housing prices / availability, good state schools and specific industries in individual seats helps determines voting behaviour. The closure of a factory with 30,000 workers or the building of new local infrastructure can radically transform the economic prospects and thus voting intentions of individuals in a seat. Recent Labour woes can be partly explained in the politics of microeconomics. Many of their voters are more educated and urbanised due to their work. This has the negative effect of clustering their votes ‘inefficiently’ in cities and universities towns, giving them huge ‘wasted’ majorities in certain seats, while thinning their vote in the north. Because the UK’s political system is First Past The Post (FPTP), many votes are essentially lost within tight and arbitrary boundaries. Therefore Labour, currently, will struggle to win a majority even with large percentage point leads (Similar to the Conservatives in 2010). In 2010, this wasn’t an issue when Brown managed to get 258 seats on just 29% of the vote — showing a remarkably efficient vote even when losing! Essentially microeconomic distribution of voters and local microeconomies can determine elections.

An example of this is an (invented) scenario in which London suffers serious macroeconomic downturn and becomes unpalatable to live in. The macro shows that voters are moving out of London to the wider areas or regions, which will change London’s economy and thus vote, as well as surrounding regions. The micro element is the distribution of who is moving out? Are they middle or lower class? How are the local housing prices being changed within and outside London? How will this effect local economies and individuals’ decisions? What jobs will this create or destroy in specific seats / industries? What seats are these individuals moving too and how will this directly change the outcome? Has the government successfully designed economic policy to target these swing voters or understand the economic shifts? until eventually you come back to the macro question of who is now going to win a majority because macroeconomic factors have changed the micro political-economic foundations to enable them to win?

To End

I’ve covered three separate areas of electoral economy. Pre-election budgets can seem like a gimmick, but considered and measured targeting has consistently proved to be electorally successful. Micro political-economic factors within swing seats, towns and villages may seem insignificant but are key in determining which seats are battlegrounds, and exactly what type of economic voter is shifting the power in Westminster. But overall, the pivotal factor is the macroeconomic conditions of collapse, perceived consensus (theory) and competency. It’s no coincidence that the ‘economic competency’ poll is still the single most accurate quantifiable stat that predicts who will an election.