The dust has settled, and the volatile moods of election week, and night, have subsided. An evening of mixed narratives failed to produce a cohesive theme, but the Local Elections of 2022 may have been a significant shift for British politics.

The Political Inquiry’s (TPI) Aggregate Election Results LE2022 UK based on BBC Data (No. Seats / Net + or -):

Labour: 3073 / +108

Conservatives: 1403 / -485

Liberal Democrats: 868 / +224

SNP: 453 / +22

Greens: 151 / +79

Plaid Cymru: 202 / -6

Northern Ireland:

Sinn Fein: 27 / No Change

DUP: 25 / -3

Alliance: 17 / +9

UUP: 9 / -1

SDLP: 8 / -4

TUV: 1 / No Change

1. Skewed Reporting Determines Narrative

The night began with signs that Labour was underperforming, with Tory losses minimal, and Labour not net-gaining seats for the first three hours. This was due to Tory-favouring seats flowing in early, with Labour experiencing expected realignment or specific local issues.

A fascinating, and important, element of election night coverage is how specific results can shape the atmosphere and mood of the evening. Sunderland is a classic example of both a seat and council having undue importance in the narrative of the evening, due to its early declaration. While it proved a recovery defence for Labour (especially considering Johnson visited a target seat here), it wasn’t exactly indicative of the evening in Northern England or even the coverage given to Labour. David Lammy (Shadow Justice) was laughed at for celebrating Labour’s hold of Sunderland, with Huw Edwards ignoring the abnormal council circumstances1.

Defence was seen as a weakness by the BBC, with the old, flawed, mantra of ‘the opposition must gain’ — clearly dispelled in the TPI preview. However, defence alone will not win a general election.

The narrative of Labour underperformance and Tory stagnation lingered for another few hours, leading to comical headlines in right-wing papers like the Express’ ‘Bullish Boris’. Right-wing ‘unconventional’ news organisations help define media narrative — indirectly influencing Westminster and bulletins on radio or the BBC website / app (arguably the single most significant UK media output). Even if the headlines are radical outliers, they succeed by shifting the conversation onto Tory over-performance, and Labour underperformance, which distract from the real question: how dire were Tory losses, and how and where were the opposition gaining?

After dawn, however, results from London and Southern seats started coming in (as well as Wales and Scotland). What followed was a possibly significant, and completely undervalued, shift in UK politics — with all the caveats that you cannot read local elections like oracles. But what if, on this instance, you can?

2. The Revolution Will Be Yellow (LD +224)

With all the necessary caveats (local issues, protest votes, two years from an election) — the Liberal Democrats had an unquestionably brilliant performance. Building off the back of its remarkable recent by-election victories, especially North Shropshire, the Lib Dems are back — and are possibly, once again, a pivotal political force in the UK.

The numerical gains made were not only impressive, but were built across the country on strong, locally-fuelled foundations. This is crucial, as what previous Lib Dem gains couldn’t show (by-elections) is — when the party resources are stretched across the country, can the Lib Dems still make big gains. Winning simultaneously in Gosport, Woking and Hull isn’t to be ignored — even if some are old hunting grounds.

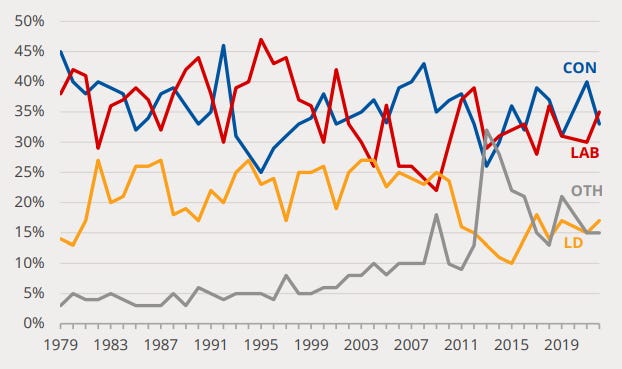

Talking to Lib Dem staffers, the mood in the party is the strongest it’s been since they entered into government. Vince Cable’s remain-inflated bubble recovery, and Swinson’s catastrophic puncturing of it, seem a distant past. Based on voting data, and ignoring the remain-specific boost in Lib Dem vote in 2019, this was their best local election since 2009, in terms of councils controlled and percentage of vote — even nearing the heights of Ashdown and Kennedy of the low 30s / high 20s.

Genuine Lib Dem recovery is paramount for the future of British politics for two reasons. Firstly, the Tories have to seriously worry about losing the so-called ‘blue wall’ (seats containing traditional Tory voters). This will require resources to be fuelled into defensive southern constituencies, reducing resources in the North / Midlands. These seats include flagship ministerial seats such as Dominic Raab’s Esher and Walton — all of which look increasingly likely to shift yellow. The Conservatives won’t want a repeat of the ‘Portillo' moment’. Secondly, the prospect of a Lib-Lab pact, and subsequent coalition government should not be underrated. One clear result of the evening was that these results, extrapolated onto the parliamentary map, show a hung parliament:

Not needing the SNP for government solves the SNP issue of a possible Scottish referendum for coalition deal. If Labour can answer the ‘SNP coalition’ question, which helped destroy Miliband’s 2015 campaign, with the answer of a Lib Dem coalition lead by a centrist ex-minister (Ed Davey), Tory attacks will wither. Furthermore, attacking a Lib Dem coalition inadvertently attacks the Tories own 2010-15 administration — a government that was somewhat popular, particularly within the party.

While the projected Labour/ Lib Dem majority may be small, if bolstered by SDLP, Green, Alliance and possibly SNP commons votes, it is certainly workable. Wilson and Callaghan governed on less…

3. A Recovery of Sorts (Lab + 108)

After terrible elections in 2019 and 2021, Labour dramatically improved. Although, in comparison to 2018 (when these seats were last elected), the improvement was more nuanced — with an overall gain of over 100 seats hiding weakness. Labour made impressive council gains in London: with Barnet, Westminster and Wandsworth (flagship Tory strongholds) all turning red. Labour continued remarkable dominance and gains in Wales — raising serious questions for English Labour. The ‘red wall’ remained hotly contested, with Labour recovery and defence, as well as weakness in realigning seats such as Amber Valley, Nuneaton, Hartlepool and Newcastle-under-Lyme.

Arguably, the West Midlands, North East / West and Yorkshire could be categorised, more accurately, as the primary swing seats in the red / blue battle. Assigning the ‘red wall’ tint obscures their distance from Labour in a traditional sense, and contends that Labour ‘should’ be winning these seats. This ignores several facts. Not only did many of these seats vote for Brexit by 60+%, but also voted for Johnson in 2019 and 2021. For Labour to hold their pre-2018 ‘red wall’ collapse, and only give ground in few areas, is a positive step, and undervalued in media coverage. However, it’s important to remember the ‘red wall’ has been (electorally) in stealth realignment since 2010 / 2015, and thus won’t show up in the 2022 numbers. So, in essence, it’s a ‘winning’ retreat — rasing questions over future strategy in the ‘red-wall’.

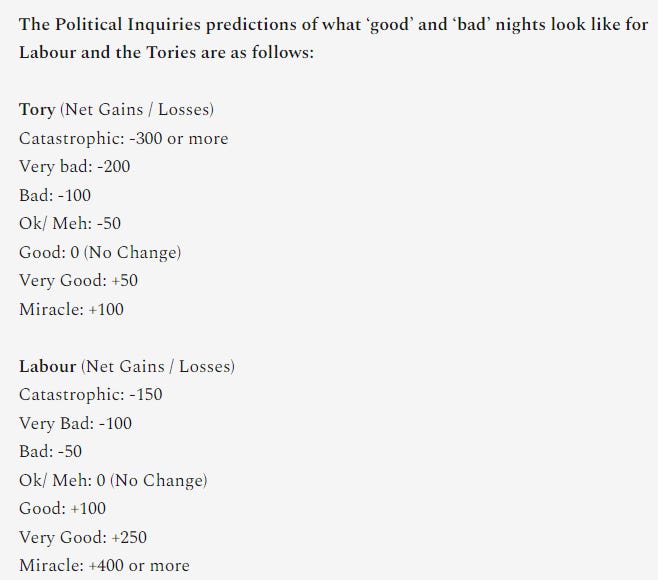

Based on TPI ratings, Labour achieved a ‘good’ night (+100), enough to confirm Starmer’s narrative of ‘road to recovery’. He has successfully detoxified the party from Corbyn, antisemitism and general economic weakness. Competency has been achieved, but what labour lacks now is vision and ideas. This prompts the question — will Starmer be a Kinnock-style figure to the next Blair, or can he actually be the next Labour PM? While it is two years out from a manifesto, and TPI understands that early commitments can sink future policy options, Labour is in a prime position to now sketch out its true vision. The cost-of-living crisis, Ukraine and Climate Change are three important problems that provide ample room to construct coherent visions. If Starmer wont, better politicians will.

Overall, Starmer should feel conflicted. Labour have recovered, but possibly not fast enough for 2024 — although no one is envious of the current Conservative position. The New Statesman has turned on Starmer, openly criticising and publishing his enemies — possibly in preparation for an entry from leadership candidates, coming after his announcement he would resign if fined for ‘beergate’. Honesty and integrity are an honourable art, but not a route to power. If you want power, it’s sometimes “better to be feared than loved” in politics2.

4. Disunited Kingdom (SF 27 and SNP +22)

The biggest power shift that occurred in the Local Elections was the dramatic victory of Sinn Fein, who have, for the first time, won in Northern Ireland. This raises the spectre of more nationalist questions on a united Ireland and a border poll. The DUP have destroyed their record on the rocks of Brexit, and are now contributing to yet another constitutional crisis over the protocol — directly in response to losing votes to the stronger Unionist parties of the TUV and UUP.

The surge of the Alliance party (non-sectarian) could begin an era of non-sectarian Northern Irish politics, with Naomi Long’s party only eight seats behind the DUP. Breaking the Nationalist-Unionist lock on the top two (which dictates the First and Deputy minister positions in the Good Friday Agreement) is now in the realm of possibility, and will trigger a need to renegotiate the Good Friday agreement as a Unionist-Nationalist lock is enshrined in law. What the 2022 Northern Irish elections illustrated was that the constitutional question of power-sharing and Northern Ireland’s position in the union (either through the protocol, the GFA or leaving the UK entirely) is under pressure.

The theme of a disunited kingdom continued in the North, with the SNP surprisingly making gains. After 15 years in government, the SNP show no sign of relinquishing power — continuing to defy the incumbent electoral cycle with the invigorating power of nationalism. However, Labour’s recovery in Scotland — led by an improving Anas Sarwar — could be the start of something bigger for Labour. With the loss of Labour’s Scottish stronghold in 2015, dreams of a majority have fallen flat. But with Sarwar’s gains and momentum building, and overtaking the Tories to come second in Scotland, he is progressing towards a chance of pivotal Labour gains in Westminster and Holyrood. Sarwar could be Labour’s version of Ruth Davidson: an unassuming Scottish politician who saved May’s 2017 campaign by capturing — against the trend — 12 seats in Scotland. Sarwar doing the same in 2024 could decide the next government.

However, with secessionist parties strengthening — still — the UK’s inadequate constitutional arrangement is once again put under the spotlight. The UK is lacking innovative ideas to hold the union together, as time is inevitably running out.

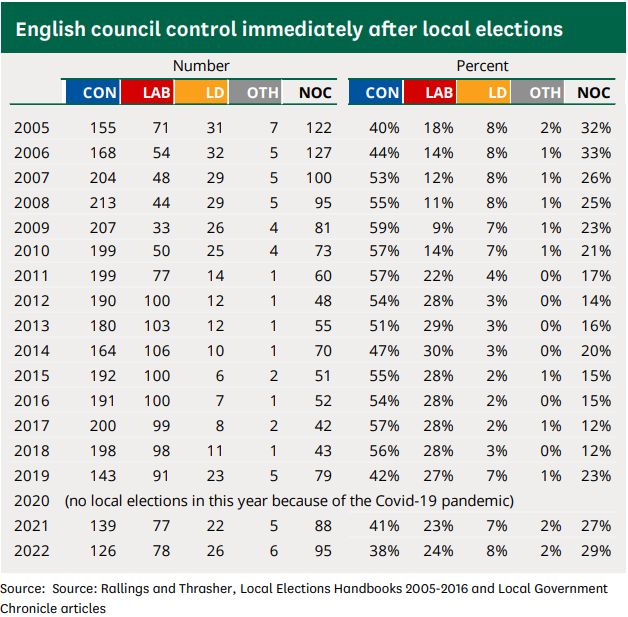

5. Blue Catastrophe (Con -485)

The Tories, remarkably, underperformed The Political Inquiry’s ‘catastrophic’ scenario (-300), to confirm a seriously dire election. Of course, the caveats of only local elections, midterm effects, economic woes (etc) all enter the conversation, but nothing detracts from the headline number — and geographical breakdown. A horrific night in Wales and Scotland confirms Conservative fears that the recent successful incursions into left-wing regional strongholds have halted, and in some instances fully capitulated. For instance, the Tories no longer control a single council in Wales.

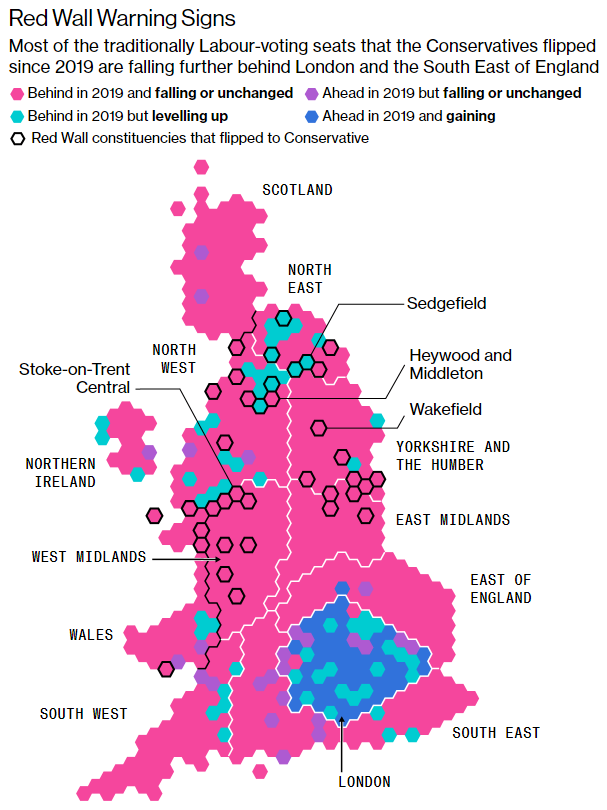

Some standout performances from newly-built local party-infrastructure, centred around 2019 red-wall MPs, produced sparks of hope — however Labour managed, without much energy or inspirational leadership, to recapture (mostly) their 2018 position. This should give Tories raging headaches, as the cost-of-living crisis is poised to turn into a full-blown emergency, as inflation soars to 9% and recession seems imminent. Underconsumption is a serious threat —both to a banker’s profits, or a Universal Credit recipients’ ability to eat. Have the Tories really ‘levelled up’ the Midlands and North in time, or just provided new coats of paint to age-old economic and social decay? Bloomberg (Not exactly a Labour ally) is firm they haven’t:3

Johnson now faces a daunting political project — worse than he’s faced in the last three years of premiership (even with Covid). He has two years to attempt to save the economy from recession, level up abysmal living standards, while retaining the classic Tory credentials of low-tax, low-spend, low-borrow and low-inflation. The Political Inquiry insists that all four of these classic Tory economic policies are fast-dissipating, or already non-existent. Keeping the rhetoric of these policies, while failing on its outcomes, is a recipe for electoral disaster — specifically in the Tory ‘blue wall’ of lower middle to upper class voters, who arguably liked the Cameron government, but are now aghast at Johnson’s style and flawed economic management. It’s in these constituencies Tory strategists fear the Lib Dem threat.

When a government loses competency on the economy, it’s demise usually follows. The economy (and ‘competency’ rating) are the two most predictable quantitative polling measures for who wins a general election. Johnson is currently losing both, and the Tories all-round dire local election performance confirms this. The Conservatives have two years to recover, with serious intellectual and innovative ideas needed to revitalise a flailing country. If not, an 80-seat majority could disintegrate overnight — the last time such a capitulation occurred was in 1970 after Wilson devalued the pound, as the then economy lay inflated and battered. Will 1970 repeat in 2024?

Conclusion

Synthesising the points discussed, LE2022 was about: Poor reporting defining premature narrative, Lib Dem strength, Labour’s nuanced recovery, Sinn Fein’s victory, SNP dominance and Tory catastrophe. From Belfast to Wandsworth, as Northern Irish government changes, there are signs the same could soon occur in Westminster.

Sunderland is a Council racked with controversy - and a three-way fight between Labour, Tories and Lib Dems. In 2021, the Lib Dems and Tories tore apart Labour, so for Labour to recover to their 2018 position was actually impressive. However, paradoxically this marked a sour night of coverage where Labour defence was demonised as lack of thrust. Actually, retaining 2018 results were good, even if general recovery was lacking.

Machiavelli - The Prince - 1532

https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/uk-levelling-up/red-wall-constituencies-falling-behind.html?utm_source=google&utm_medium=bd&utm_campaign=Pol&cmpId=GP.Pol