As political historian Anthony Seldon argues in his Times essay, Prime Ministers are brought down by scandal, coup or policy failure. Johnson’s implosion included an “unprecedented cocktail of all three”.

The direct trigger of Johnson’s ugly demise was the continued promotion of Chris Pincher, an alleged sexual assaulter, to the privileged position of deputy chief whip. This became a scandal too far for the ‘herd’ of Tory MPs when the BBC broke the story that Johnson actively knew about the allegations when promoting him. The stampede began, and it was not to be stopped. Over 72 hours, beginning with Javid’s bold resignation and Sunak’s opportunistic support, 62 members of the government quit. Johnson gruelled out his last hours in power, scraping through new ministerial appointments, clinging on in PMQs and battling the Liaison Committee, all while using his natural defence of obfuscation and bravado. But this time, the Tory MPs were not for turning. Johnson failed to stem the flow and eventually resigned. The war of attrition was lost.

Scandal

What began with the flawed handling of the Patterson scandal, continued into Partygate and culminated in the Pincher allegations. Constant mishandling with no contrition. What hurt Johnson was never just the scandal, but always the failed cover-up. A PM can’t survive endless scandals that include lobbying, sexual assault and illegal piss-ups. This wasn’t like Johnson’s past misdemeanours of affairs or buffoonery — instead these were examples of poor leadership and a callous disregard for morality. As Mayor and Foreign Secretary, Johnson could get away with it. As Prime Minister, he could not.

The general atmosphere in the Tory party that enabled Pincher, but also Khan (sexually assaulting an underage boy), Parish (watching porn in Parliament), Hancock (breaking social distancing for an affair) and now Warburton (alleged sexual assault and cocaine usage), was set from the top. Parish and Khan’s resignations forced two by-election defeats which were pivotal in turning MPs on Johnson as they realised their seats were in danger. Johnson’s boosterism and moral insouciance propelled him into No.10, but it also became his downfall.

Policy Failure

Johnson’s premiership truly hit the rocks when it achieved an 80-seat majority and passed the Brexit deal in January 2020. After this, there was no plan, no ideology and no strategy to use the power of the office to transform the country. The largely blank 2019 manifesto foreshadowed Johnson’s empty policy agenda. Johnsonism will be regarded as the ambition, and attempted retention, of power — not an ideology or a plan for governing. Similar to Machiavelli, except, while Machiavelli used the ruthless edge of political power to achieve ends, Johnson preferred the non-combative bluster of boosterism for no clear goal except to increase his own power. After becoming PM there were no more ladders of his Cursus Honorum to climb; evidently explaining his lack of ambition to achieve more when, in his mind, the pinnacle had already been reached.

As Covid hit, Johnson was left floundering. Three late lockdowns demonstrated his inability to focus on governing. In addition, his, and Sunak’s, libertarian nature caused the unmitigated disaster of economic stimulus in the Summer of 2020 (Eat out to help out), catalysing a horrific second wave. This is Johnson’s true Covid legacy. Vaccines and furlough, while curated under Johnson’s watch, were hardly attributable to his actions. Johnson’s lack of engagement and grasp of detail, matched with his libertarian beliefs, ensured he was possibly the worst PM in recent history (since Eden / Chamberlain) for a crisis, let alone a pandemic.

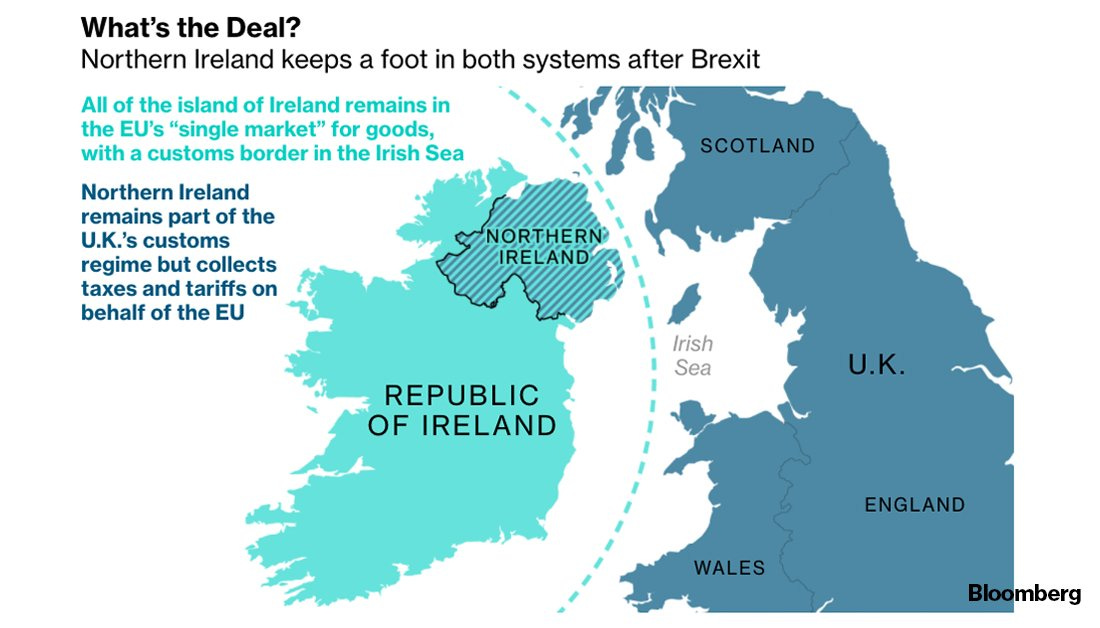

A constant distraction during Covid was the rumbling negotiations of Brexit. Attaining an exit and trade deal with the EU, even if its benefit is currently negligible, was impressive. However, the side effects of the deal for unionism (by separating Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK) and the protocol breaking up the Northern Ireland executive, is not, in any calculation, a policy success. As this is being written, Northern Ireland still has no government due to Johnson’s deal, where the protocol has divided this region once again on sectarian lines. For someone who studied a form of history at Oxford, one would expect a better grasp of the sensitive legacy of civil war and the importance of the Good Friday Agreement.

However, the final undoing for Johnson on policy was the post-Covid economic downturn. War in Ukraine and international supply chain issues ensured high inflation, peaking under Johnson at 9.4%. Brexit’s economic fallout and years of uninventive Treasury policy has left the UK economy with no substantive growth. Johnson’s politics of pure power, with no real strategy, desire to govern or serious economic policy, has helped push the UK economy into stagflation. When the economy goes, as argued by TPI, the government usually collapses, or defeated at the subsequent election. It is no surprise that Johnson’s downfall was hastened by his lack of successful policy.

Coup / Personnel

Johnson’s team has gone through three revolutions in just three years. Johnson has expended three Chiefs of staff (CoS), three Chancellors, four Education secretaries and two ethics advisors.

Dominic Cummings (Chief Advisor / de facto CoS) and Lee Cain’s (Chief of Comms) departure in November 2020 was monumental. After losing a power struggle with Symonds and Johnson, the Vote Leave duo exited unceremoniously. Cummings proceeded to wage siege warfare against Johnson, notably his May 2021 incendiary committee appearance on Covid and alleged leaking — particularly on partygate. Cummings was the last person with enough power in No.10 to say ‘No’ to Johnson, with the only other being Levido in the 2019 General Election. As soon as this directional force exited No.10, and Johnson was allowed to free-roam on convention, policy and morality (even more so than under Cummings), his premiership faltered.

No real policy was achieved in the recovery year of 2021 with his second team. Instead, Johnson’s politically lacking CoS Rosenfield, and thoughtful but inexperienced Cabinet Secretary (CS) Simon Case (after he had fired his previous CS Sedwill), struggled to direct Johnson’s erratic energy into anything productive. Key delivery ministers, like Michael Gove or Julian Lewis, were side-lined. Instead, political yes men/ women were preferred with the likes of Rees-Mogg, Patel, Truss and Dorries. Loyalty, not governing skill, was the desired quality — again illustrating how Johnsonism epitomises the desire for power and not the responsibility of the governing that comes with it.

Allegra Stratton, another Comms advisor, was sacrificed as an attempt to shield Johnson from his Partygate mess. However, as Partygate persisted, Johnson was forced to cull the remainder of his flawed second team — with Rosenfield, Doyle and Reynolds resigning as scapegoats. One anomaly was Munira Mirza’s (Head of Policy) resignation, who was a key Johnson ally. Mirza represented the last vestiges of vision in government, and also illustrated the danger Johnson was in as even die-hard allies jumped the sinking ship.

Johnson’s third and final team, nominally lead by Steve Barclay as CoS, was heavily influenced by Lynton Crosby and David Canzini, the Australian political ‘masterminds’ that aided Cameron from CTF. Guto Harri completed the team as Chief of Comms. This team was ineffective, largely because the premiership was inevitably doomed. However, the team’s style was more akin to guerrilla warfare rather than governing — putting No.10 in a constant pseudo-election mode where wedge issues, and not serious policy, supposedly won them points or seats (evidently, they did not). The pre-Pincher relaunch of Johnson’s premiership unsurprisingly failed. Johnson continued to lie and bluster, with little change. Renewal was impossible without humility.

For the Tory party, and the leadership dreams of influential Cabinet members, enough was enough. Johnson had dispensed too many advisors, failed on too many policies, angered too many influential politicians and, ultimately, had corrosively destroyed his standing with the public (seen in by-elections and local election defeats).

Javid wielded the dagger, but Johnson created the conditions for the stabbing. It was a political downfall that was unbelievably quick and violent just two and a half years after winning an 80-seat majority.

The Legacy

Johnson has been the most important single figure in British politics for the last decade, enshrining his name up there with Thatcher, Blair and Churchill as cults of personalities. But unlike those PMs, Johnson has few governing achievements to show for it.

His key victory was Brexit, a decision with such enormous ramifications for British politics that the policy in itself ensures Johnson will be both remembered and debated in political history for decades. Lesser achievements on Ukraine, vaccines, the environment, furlough and a landslide election victory are important, but not enough to categorise him as a great or good PM. It requires minimal analysis to understand how his defenestration of the office of Prime Minister counterbalances all of his achievements in government, apart from Brexit.

Johnson’s historical importance, and performance, is somewhat similar to Heath’s: with four years (three in Johnson’s case) of badly handled crisis, economic woes, scandal and constant U-turns. Heath began his premiership as a proto-Thatcher and ended it confused in Keynesian economics with a Baldwin-esq union combativeness. However, the greatest parallel is Heath’s decision to bring the UK into the EEC (later the EU). Johnson mirrored Heath, ensuring the UK left the EU. For both Prime Ministers, their European policy had / will have the most influence on their legacy. Heath’s ideological confusion, as with Johnson’s moral degradation of the office, were / will be transitory.

The Conservative party must now embark on a difficult period of renewal if it wants to remain in power for the foreseeable future. The task is enormous. Johnson is gone, as he remarked, “for now”, but his spectre will haunt the Tory party for decades. A new era in politics has begun, but the question now is who will shape it?