State of Play: The Truss Effect

British politics is once again engulfed in crisis as a new government grapples with the UK’s economic woes

Truss’s entrance into No.10 has ushered in more continuity than it seems. Yes, ripping up economic orthodoxy and dismantling Johnson’s legacy are both ‘new’ approaches to policy. However, the Tory party is still ridden with infighting, the economy continues to worsen and the government’s chances of reelection are at an all-time low.

However, one thing is new. The staunch Conservative trait of ‘continuous revolution’ to reinvent and renew within government is, for the first time, producing negative results. Major’s post-Thatcher reinvention eventually stabilised the economy. May’s ‘burning injustices’ speech edged the Tories further towards interventionist Conservatism; which Johnson fully embraced and reinvented with the shift to ‘levelling-up’ economics and subsequent destruction of the Red-Wall. All three of these PMs (to varying degrees) went on to win elections. For the first time, however, this reinvention is severely damaging the party and it’s prospect of power.

Have the Conservatives really busted their most successful electoral trait?

The Economics: The not so mini-budget

The birth of Trussonomics hardly began when Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng delivered his bashful and bold budget. Instead, Liz Truss’s beliefs originate in Reaganomics, envisioned in the papers of the IEA and built on the foundations of Thatcherism. However it’s important to note, Trussonomics isn’t a pure attempt at reheated Thatcherism. While Trussl happily uses her pseudo-Thatcher persona to present ‘Iron will’ and tough economic reform, what she is actually proposing is (currently) unfunded and dramatic supply-side reform.

In comparison, Thatcher was much more interested in fighting inflation, tackling the money supply, balancing the budget and structurally shifting industry and society to the private sphere. Trussonomics is substantially different, namely because the UK is mostly a privatised economy, and put simply: you can’t privatise things twice.

So, how does Trussonomics compare to its true inspiration: Reaganism? While President Reagan similarly deregulated and cut taxes, he, unlike Truss, did this with the strength of the world reserve currency of the Dollar and a burgeoning American Empire. Reagan also passed several of his Tax reforms in 1986 on the backdrop of a large collapse in oil prices – making growth and economies easier to fuel with cheaper production and transit costs.

A more appropriate historical comparison is arguably the then UK Chancellor Barber in his 1972 budget. With the support of Prime Minister Heath, Barber devised his “dash for growth budget” on a similar background of inflation, stagnating growth and high fuel costs due to foreign wars. The Chancellor proceeded to cut income tax, purchase tax, relax monetary policy, while also deregulating UK bank's lending rules (later causing the credit explosion). Unfunded borrowing resultantly increased from £1 billion to £4.5 billion by 1972-3. Barber stated, in the same ilk as Kwarteng, that tax “too often stifles enterprise”. It was an ideological shift and economic gamble in the same vein as Trussonomics. In other words: a war on tax. Barber’s gamble, however, ended not in boom but bust, with inflation peaking at 20%, minimal growth and a pound which crashed 15% over the next 18 months. What drove Barber, as with Truss, was a desire to intensely push supply-side reform (deregulation and tax cuts) to grow the economy. But both embarked on the gamble with weak macroeconomic foundations.

A set of more cynical takes on what drives Trussonomics comes from Curry:

“1. They are zealots who don’t realise that the ideas they have believed in for decades are no longer fit for purpose.

2. Or they are working a clever plan to create a crisis to force further cuts in the size of the state and of public spending.

3. Or they realise that they are only going to get one shot at this, and they have decided to help their friends and political supporters cash in before the house comes crashing down around their ears. (Corruption, in other words).

4. Or they aren’t very good at politics.”

The first option seems the most likely, fitting with our overall argument as well as Truss and Kwarteng's own polemical Britannia Unchained, is that Trussonomics is based on the stuff of flawed neoliberal dreams. The second point insinuates that Truss and Kwarteng have strategically devised a long-term plan to frame how decisions are made, and thus a way of strategically passing cuts. It also assumes Truss and Kwarteng have read academics such as Lukes on theories of power and decision making (third-face of power framing). Judging from the rookie political mistakes of the Goveite rebellion and market crash, this is clearly not the case. The third option seems possible, especially with the dire prospects for the government’s reelection chances, however corruption is much more effective when done by a stable and discreet government – Truss’s style of patronage is obtuse and obvious, thus reducing its overall effectiveness. This leaves the fourth option, which is obviously correct, but is tangential to the first three options.

Regardless of which is the true driver, none of these four options are exactly endearing to the government’s policy or competency. With that said, It’s too early to tell if the economic part of Trussonomics will end as badly as Barber’s dash for growth; but Truss’s blind courage has already proven a catastrophic mistake for the political hopes of her new government.

To read more discourse on the budget, I recommends two pieces from two brilliant economists: Tooze and Weldon.

Additionally, Bourne and Bradwell supply interesting, if flawed, counter-narratives on Trussonomics that are also well worth reading.

The Politics: Death by a thousand cuts

As I explored in SOP #8, Truss was always going to struggle to achieve her economic vision. But few realised just how catastrophic the first few weeks would be. Here’s how the politics of Trussonomics first played out, and how it may continue to do so over the short and long-term:

Firstly, to ensure the Treasury would acquiesce to its own destruction of its hard-won economic record, Truss fired Tom Scholar – the Permanent Secretary of the Treasury and arguably second most powerful Civil Servant in the country. With this execution of such a useful economist (a specialist in calming markets and stakeholders), Truss made clear that she was willing to destroy anyone or anything in the Civil Service who desired to block her economic reforms.

Secondly, as also predicted, there was serious discontent and rebellion within the party. Luckily for Truss, only Gove and Shapps seem to be the public figureheads of the ‘anti-growth’ coalition to block her most radical tax cuts. However both, as demonstrated by forcing Truss to U-turn on the 45p rate, are canny and accomplished politicians. With the prospect of a larger figurehead of Sunak or Johnson still yet to join the fight publicly, Truss can only hope that it remains a Goveite rebellion, otherwise her parliamentary problems will quickly become terminal. With the return of parliament this week (10/10/22), the plotting will only increase.

Thirdly, I and others (bar Rishi Sunak), didn’t expect such a harsh attack on Sterling – dropping as low as $1.03 against the dollar after the mini-budget. Now added to the list of the several economic woes of the UK, a weak pound increases inflation as imports become more expensive. Market turmoil has also triggered a dramatic increase in Gilt yields, making government debt even more expensive to service. Trussonomics, ironically a ‘pro-business’ ideology, spooked markets so much that the Bank of England had to initiate emergency QE to save pension funds from crashing, as a series of margin calls sucked money out of the market. With the Bank’s emergency QE set to end this Friday (14/10/22), market turmoil could quickly transition to catastrophic crash if Truss cannot stabilise nerves.

Fourthly, this is only the first stage of the Trussonomics rollout. To fund these cuts and stabilise the market Truss will have to cut spending in several departments – notably welfare and benefits. Kwarteng will also be forced to publish an OBR forecast on November 23rd (at the latest) detailing the economic impact of government policy. Truss will have to pass this and the next budget over the next few months, while also forcing through tough spending cuts. For some, after seeing the response to phase one, this is mission impossible (except starring Kwasi Kwarteng and not Tom Cruise). For those who subscribe to Curry’s third argument (see above), this is the exact fight Truss wants to have. However, this fight is nonsensical after years of austerity, and obviously not winnable in a parliament which is hung, as Rawnsley notes:

“On paper, Liz Truss commands a hefty Commons majority of 71. In practice, she is a prime minister with a majority of less than zero. We have what is effectively a hung parliament in which the Truss faction is not even the largest party”

Similar to Thatcher in 1979, the Prime Minister leads a minority faction in parliament. Truss would be wise to note the political strategy and circumstances which enabled her idol to eventually forge such tough economic reform. The key differences are: Thatcher won an election (not inheriting a 12-year-old government), required a lucky war (Falklands) to survive and needed 3-4 years between 1979-1983 to even begin passing her greatest reforms through the Cabinet and Commons. It was only after four years in government and two election victories – including a landslide in 1983 – that ‘Thatcherism’ began to take its form that is so lauded over today. What unites these circumstances for Thatcher’s success is simply time. Truss’s ability to buy time and space for her reforms will be the make-or-break factor of her premiership. If she fails, her premiership is as good as dead.

Electoral Wipeout territory

Why is this such a shock? Well, take a step back and imagine this: it’s remarkable that a government, after winning a landslide 80-seat majority, would ditch their entire mandate, strategy and personnel, purely because of ideological inclination. Yes, the economy needs a jolt through reform – possibly even through a reduction of taxation on the middle-to-lower classes, who are currently experiencing the highest tax levels since 1945. However, no one would argue, especially not Thatcher, that instant trickle-down shock therapy is the easiest way to kick an economy into gear. Neither is it a way to get reelected, especially after so many economically left-wing voters of the Red Wall backed the Tories in 2019. One could argue it was Johnson’s strength and Corbyn’s weakness that ensured that large majority, however a government is always elected on it’s economic competency and policy (levelling up), rather than the simplistic presidential politics of image or performance.

It would be fair to conclude that Johnson’s downfall was hardly due to his economic policy (although this played a part on the backbenches). The real reason Johnson fell was his endless scandals leading to a coordinated coup, but more fundamentally: his inability to build a coherent No.10 team and a general lack of policy direction / delivery (as analysed in SOP #7).

And yet the Conservatives have decided to switch their traditional ploy of reinvention to seek reelection, to something more ideological. A quasi-religious reformation of both party and country, seeking purity over substance. Rather than electing a ‘winner’, such as Johnson in 2019, the Tory membership, and a third of their MPs have unleashed a force they cannot politically control: the vitriol of an open market. In a deal with the devil, the market will both giveth and taketh. For Truss’s reelection hopes, she can only pray that further actions and announcements can stabilise the economy, thus allowing time for her supposed ‘growth’ reforms to work.

This is dangerous territory for the Conservatives which is a party not comfortable exploring actual ideology, and more suited to pragmatic muddling through. Anyone versed in Thatcher’s exploits will know that her creation of an ideology was more so a melding of several contradicting ideas and reforms: ranging from traditional aspects of neo-conservatism to the brave new world of neoliberalism. It was, strategically, something closer to Johnson’s cakism, rather than puritan Trussonomics.

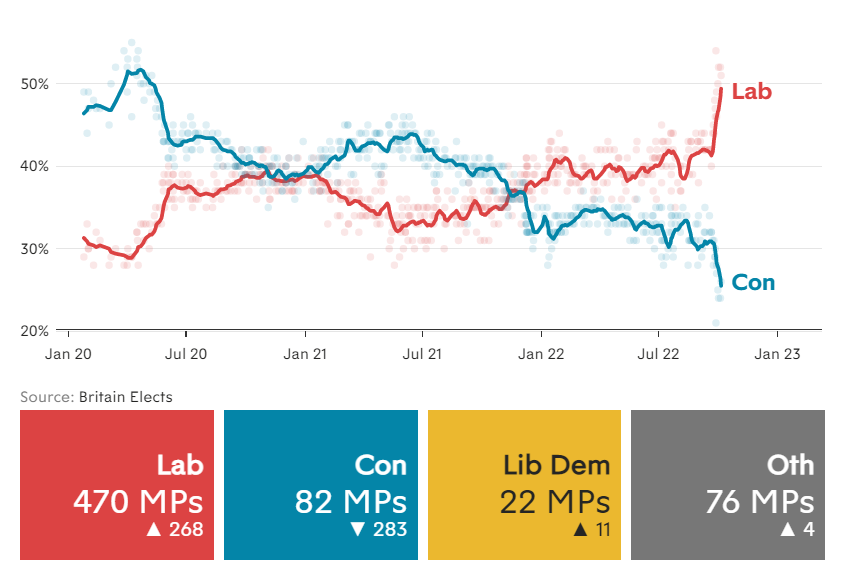

Unsurprisingly, the country dislikes it when the perceived boring-party of government starts to have seriously expansionist and bold ideas on reform, which subsequently causes an economic crisis. At a time of economic decline, and with a country at its most left-wing (economically) for 40 years, this gamble of Trussonomics looks foolish. After a near-perfect conference for Starmer, his boring and pragmatic style matched with big-government intervention seems a potent mix. Burnell is right arguing that Labour can now capture the ‘growth for good’ narrative Vs Truss’s ‘growth for greed’. Labour, as a result, now lead in every poll by over 20-30 points. These numbers are akin to those of Tony Blair in 1997, and if they remain even close to this will result in a three-figure landslide victory for Labour in 2024. See LS#2 for more on Labour.

A quiet time in opposition, however, might be the best-case scenario for the Conservatives. A time of rest and rejuvenation is needed for a party exhausted with 12 years in government, out of workable ideas and bitterly divided. Opposition will allow wounds to heal and new blood to come through the ranks. This, as some in the party realise, would be ideal.

But, more worryingly for the Tories, their poll numbers are so drastically bad that an utter wipeout of the party itself is, somehow, on the cards. If numbers continue to worsen, Truss will likely be ditched in favour of a unifying PM; someone elected simply to ensure the party’s survival. Although a 1979 SDP-Labour style split is still a possible outcome if the two sides of the party (Goveite Vs Trussite) can’t be reconciled in time for the next election. A Tory result of under or around 150 seats could spawn another party designed to replace the Conservatives.

Murmurs of an ‘En Marche’ style party on the centre-right (Culturally / authoritarian right but economically left-wing), possibly masterminded by Cummings and the Vote Leave team, are getting louder, but are still muted. Due to the UK’s electoral system, any new party would struggle to breakthrough. But a serious launch would certainly pose a possibility of making the Conservatives-in-name-only party extinct by splitting the right-leaning vote. These are similar images which prompted Cameron’s Brexit-pivot to save the Tories from electoral defeat (due to UKIP) between 2013-2015.

Truss is in a race to save her career, party and the country before Christmas. As a harsh winter begins, only time will tell if the economic path she has chosen will reap the rewards she so desperately needs. But, as for the politics, Truss is already engulfed in civil war. All the Prime Minister can hope for is that further action can stabilise the markets and, somehow, buy time for her reforms to produce the magical antidote to the poisonous politics of the Tory party: Growth.

To read further on this subject TPI recommends:

Andrew Curry’s long read provides the best long-term perspective analysis on Trussonomics and the politics of time.

Phil Burton-Cartledge on reinventing Toryism for ideas on what a new Conservatism could look like.